Ana María Loose[1] y Miguel Ignacio Gómez[2]

[1]Ecology Project International, [2]Cornell University

Figure 1. During field trips with park rangers, students help newly hatched tortoises leave their nests. Photo: EPI Archive

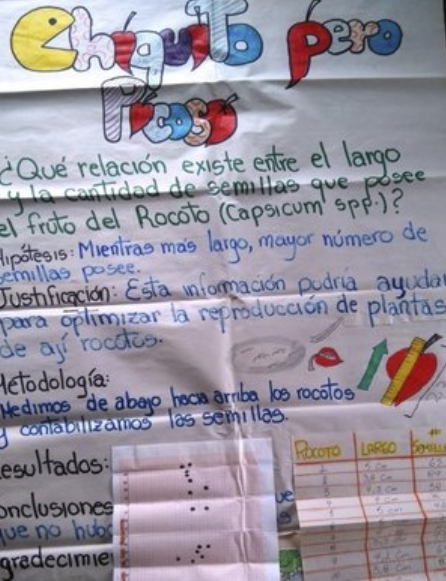

Is there a correlation between the size of an aji chili pepper and its number of seeds? This is the question that occurs to Alejandro, a second-year high school student at the Colegio Nacional Galápagos, when he sees a plant full of peppers of different sizes in the Pájaro Brujo Reserve on the island of Santa Cruz. It is the second day of an outdoor ecology field camp.

In contrast to conventional classroom education, this question wasn’t asked and won’t be answered by the teacher. Rather, it originated in the observations of a 17-year-old student, who will answer the question himself using tools he learns during the camp.

The Galapagos National Park Directorate and Ecology Project International (EPI) have organized annual outdoor ecology camps since 2014. The camps take students from throughout Galapagos out of the classroom to remote sites on Santa Cruz, where they work hand-in-hand with scientists and park rangers to protect threatened species. We focus on inquiry-based experiential learning because we believe that this approach can result in significant changes in the environmental knowledge, attitudes and skills of participants.

In partnership with Cornell University, in 2017 we developed and implemented a quantitative assessment of our ecology camps, with the goal of assessing their impact on students’ environmental literacy. We wanted to know how much students learn and change by participating in science-focused experiential learning.

WHAT IS ENVIRONMENTAL LITERACY?

There are many definitions of environmental literacy. EPI uses that of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the North American Association for Environmental Education (NAAEE). These organizations define an environmentally literate person as someone who demonstrates the knowledge, dispositions, competencies and behavior to act, individually or collectively, to address environmental challenges.

An environmentally literate person is someone who volunteers his or her time to join or lead a green initiative at school or in the workplace. It is someone who understands the problems associated with plastics and decides to use reusable water bottles.

EPI uses the Environmental Literacy Wheel (Figure 2) to depict the main components and sub-components of environmental literacy. This visual reminds EPI’s educators of topics to include in each lesson and activity throughout our outdoor ecology camps. By the end of the camps we expect student participants to have developed knowledge, dispositions, competencies and behavior associated with increased environmental literacy.

Figure 2. EPI’s Environmental Literacy Wheel.

THE ECOLOGY CAMP CURRICULUM

Over a four-day period, students immerse themselves in a curriculum designed to strengthen their understanding of the fragility of Galapagos and the planet. During the camp they have no contact with their families, and they are prohibited from using electronic devices. Through experiential learning — learning-by-doing — they come to understand concepts such as ecosystem interdependence, endemism, dispersion, invasive species, climate change, ecological footprint and consumer habits.

In the mornings, students participate in field trips with park rangers and scientists. We place special emphasis on the unique role of the Galapagos giant tortoise in island ecosystems. For example, to better understand tortoises’ role in distributing seeds of native and invasive plant species, students help Dr. Stephen Blake of the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology to collect tortoise scat and identify the types of seeds found in each sample (Figures 3 and 4). During 2017, students identified and cataloged a total of 28,458 seeds.

Figure 3: Using sieves and tweezers, students separate and identify seeds ingested by tortoises. Photo: EPI Archives

Figure 4. Dr. Steve Blake teaches a student how to record the location where a scat sample was found, for future analysis. Photo: EPI Archive

To gain a better understanding of tortoise survival indices, students help park rangers collect biometric and health data from the two Santa Cruz tortoise species: Chelonoidos porteri, which inhabits the western part of the island, and Chelonoidis donfaustoi found in the east. Students also participate in a tortoise movement study conducted by Washington Tapia, a biologist who leads Galapagos Conservancy’s Giant Tortoise Restoration Initiative in coordination with Galapagos National Park personnel.

Our students contribute valuable volunteer hours in the field and are directly involved in research and management activities that have increased the numbers of tortoises tagged, identified and monitored. The data collected by students is used to better understand tortoise population trends and possible threats to their survival. Throughout this process, scientists and park rangers serve as role models and mentors for the students, sometimes influencing their career aspirations.

Figure 5. Monitoring a giant tortoise is a unique and unforgettable experience for students. Photo: EPI Archive

In the afternoons, EPI educators and park rangers work with students as they analyze data collected during the morning and develop questions and hypotheses to design their own research project. In one of these sessions, Alejandro rejected his hypothesis that “the bigger the pepper (Capsicum spp.), the greater the number of seeds,” after analyzing his data (Figures 6 and 7). Such experiential learning based on practical experience is never forgotten.

THE STUDENT PARTICIPATION PROGRAM

The ecology camps are part of the Ecuadorian Ministry of Education’s Student Participation Program, which requires that all students in their last two years of high school conduct 100 hours of volunteer community service annually as a prerequisite to obtaining their diplomas. Students working with the National Park and EPI have chosen to focus their 200 hours on environmental action; other options include health, art and culture.

THE PARTICIPANTS: BEFORE AND AFTER THE CAMPS

We have long believed that experiential learning, singular contact with Galapagos flora and fauna, and time spent outdoors provide a powerful way to achieve profound changes in the environmental literacy of young people. To measure student learning, we worked with researchers from Cornell University to review and adapt existing EPI evaluation tools.

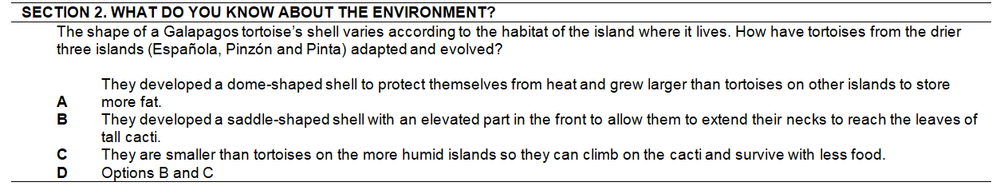

Prior to the 2017 camp, students completed a pre-camp questionnaire. The 11 knowledge-based questions focused mainly on ecological systems and environmental challenges (Table 1).

Table 1. Sample knowledge question on the 2017 Pre-camp Questionnaire.

Questions related to dispositions focused on environmental awareness, personal responsibility and motivation to act (Table 2).

Table 2. Sample disposition question on the 2017 Pre-camp Questionnaire.

The competencies section (Table 3) focused on the scientific method taught during the camps. While this questionnaire represents a subjective self-assessment, responses were compared to the scientific skills students demonstrated during the data collection and research project development activities during the camp.

Table 3. Sample competency question from the 2017 Pre-camp Questionnaire.

We used the results of the pre-camp survey to establish a baseline of knowledge, dispositions and competencies.

The post-camp questionnaire, which measured the same variables, was administered on the last day of the camp. Questions related to changes in behavior the Environmental Literacy Wheel were not included because measurement would need to occur well after the camp in order to observe meaningful changes.

All 167 participants in the 2017 camp completed the questionnaire (17 students from Isabela, 51 from San Cristóbal and 99 from Santa Cruz).

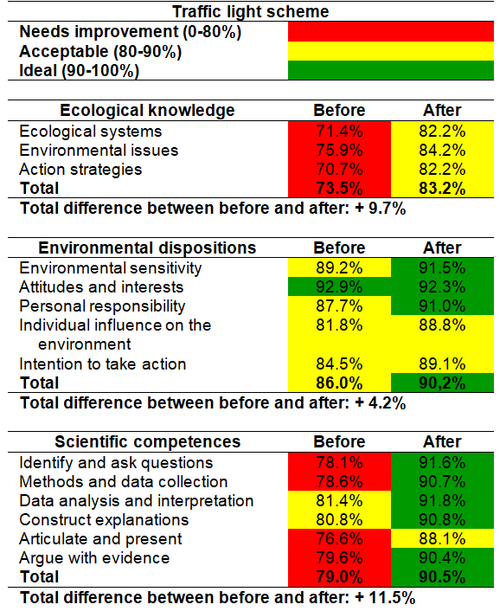

For each variable measured, we established a maximum possible score of 100%. We used students’ pre- and post-camp scores to calculate overall student averages for each variable, which were represented as a percentage of the highest possible score. Using a traffic light scheme, we established a three-level scale: optimal (green), acceptable (yellow) and needs improvement (red) (Table 4).

At the end of the camp, environmental dispositions and scientific competencies were the areas with the highest number of variables scored as ideal or green (Table 4). We observed the greatest changes in learning in the areas of environmental knowledge and scientific competencies, with average increases of 11.5% and 9.7% respectively (Table 4).

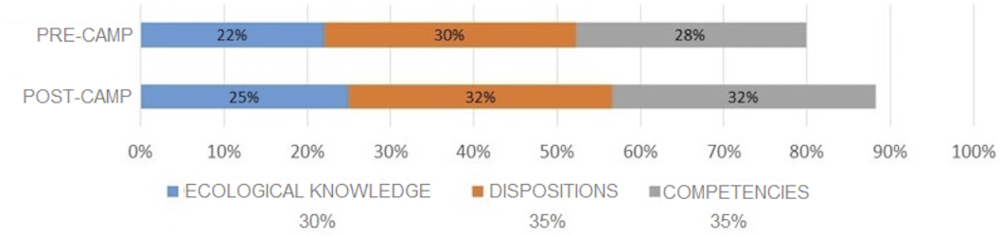

To establish an environmental literacy index, we weighted variables as follows: knowledge 30%, dispositions 35%, and competencies 35%. We calculated the total percentages in each category pre- and post-camp to determine growth in students’ environmental literacy (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Student environmental literacy before and after the ecology camp.

One-hundred percent was the highest possible environmental literacy score. Before the camp, student environmental literacy reached 80%, leaving 20% for possible growth. By the end of the camp, students raised their environmental literacy by 8.4%, representing a 42% increase in environmental literacy (Figure 8).

EXPERIENTIAL EDUCATION: A SUCCESSFUL MODEL IN DANGER OF EXTINCTION

According to this evaluation, environmental literacy increased among the young people who participate in our ecology camps. Our experience can serve as a successful, replicable model not only for changing student attitudes toward the environment, but also for strengthening their ability to analyze information and make decisions.

While there is general agreement that high-quality education is important for the sustainability of our planet, fewer and fewer resources are available for environmental education. This is especially the case for programs focused on experiential learning, which tend to be more expensive because of costs associated with transportation, field equipment, staffing, etc. While the ecology camps form part of the Ministry of Education’s Student Participation Program, they are financed by international donors. Funding challenges threaten the long-term continuity of this educational model.

Because of these challenges, it is essential to demonstrate the long-term impact and effectiveness of experiential education programs. Tools to measure behavioral change could further improve our evaluation of environmental literacy, providing insights into long-term impacts of environmental education programs. EPI is currently reviewing its evaluation tools and plans to administer a questionnaire 12 months after each camp to measure changes in participant behavior. We are also developing an App to measure the ecological footprint of former participants.

LIFE AFTER THE ECOLOGY CAMPS

Figure 9. Members of EPI’s ecology club receive training in sea turtle monitoring. Photo: EPI Archive

After completing the four-day camp, students serve as volunteers with the Galapagos National Park Directorate for 100 hours on Saturdays over a three- or four-month period. They help reforest areas with native and endemic plants and set traps for invasive species such as rats and ants. At the end of the program, they return to their schools to implement their own environmental initiatives. Some examples of student projects include native gardens and campaigns to reduce plastic waste.

Many students return to EPI looking to participate in new environmental initiatives. In 2012, we established an ecology club that has become a home for former camp participants who seek to take an active role in conservation in Galapagos. For us, this is one of the best indicators that the camps have fulfilled their purpose.

“THIS WAS AN UNFORGETTABLE EXPERIENCE THAT ALLOWED ME TO INTERACT WITH NATURE AND INCREASE MY AWARENESS OF HOW HUMANS IMPACT THE WORLD.”

~ Galapagos Student