José Guerrero Vela and Ashleigh Klingman DeFever

GECO (Grupo Eco Cultural Organizado)

Figure 1. For more than 10 years, the community association GECO has inspired social change through an interdisciplinary approach. From left to right: Daniela Chalén, Leidy Apolo, Ashleigh Klingman, Carolina Velasteguí, José Guerrero and Roberto Vera. Photo: GECO

This is a story about a group of women who have been leading a long-term campaign against plastics on San Cristóbal Island. Daniela Chalén, the daughter of a Galapagos fisherman, was born on a plane between Galapagos and continental Ecuador. She was literally born flying! Leidy Apolo was born in Zaruma, and ever since becoming a mother in the Islands, she has focused on reducing her ecological footprint. Ashleigh Klingman is a native of the United States, but for 13 years she has been a Galapagueña at heart who found love in the islands. Carolina Velasteguí is from the Ecuadorian capital, but while she was working on her thesis in the highlands of San Cristóbal, the Islands worked their charm and embraced her as a new inhabitant. These four women are all mothers, entrepreneurs, and determined community leaders who have coordinated an education and community engagement strategy to promote the reduction of plastics.

Daniela formed GECO (in Spanish: Grupo ECO Cultural Organizado) more than 10 years ago with the help of others from Galapagos, mainland Ecuador and Spain. Over time, Carolina, Ashleigh and Leidy began to contribute their skills, energy and experience.

At the beginning of 2017, GECO set the goal of changing local behavior to reduce the use of plastic by different sectors of society. We selected this topic because of the impacts of plastics on local biodiversity, on the economy, and on health of the human population (Auta et al. 2017). This article shares the achievements and lessons learned by the “Going Back to a Plastics Free Ocean” project.

OUR STRATEGIES

By empowering organized groups of citizens, GECO seeks to promote values and lifestyles that that are consistent with a healthy population and environment.

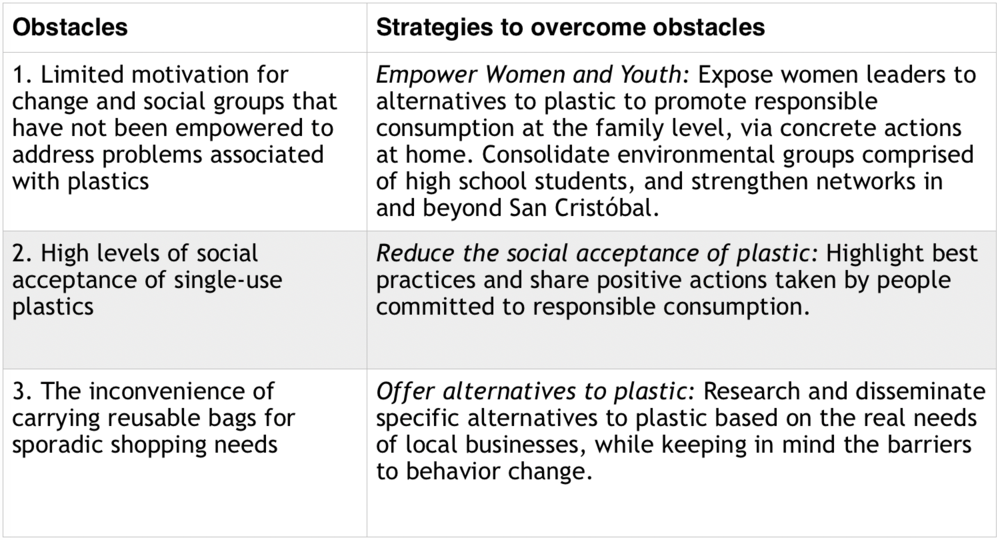

The Going Back to a Plastics Free Ocean project applies a methodology known as community-based social marketing, which has been used internationally in programs that seek to change environmental behavior (McKenzie-Mohr et al.2011). This methodology involves identifying obstacles to desired behavior and implementing different strategies to overcome those obstacles (Table 1).

Table 1. Strategies related to important obstacles to behavioral change identified in San Cristóbal.

We focus primarily on women as agents of change and as a target group. Women are key to reducing the use of plastics because in most countries with emerging economies, they are responsible for buying consumer goods such as food and household products (WECF 2017).

EMPOWERING WOMEN AND YOUTH

ALLIANCES THAT MULTIPLY

Figure 3. Participants from San Cristóbal and Isabela at the end of a training workshop in the Tribes methodology. Photo: Ashleigh Klingman

To strengthen the leadership of local women educators, GECO organized a workshop on “Tribes Learning Communities,” a methodology that promotes teamwork. During the event, 22 educators from Isabela and San Cristóbal Islands learned strategies to foster collaborative work and at the same time to promote recognition of individual responsibility for solving problems. Participants had the chance to apply techniques for achieving consensus and for forming small groups with specific individual responsibilities. They can now use these techniques to mobilize their students in plastics reduction campaigns in their classrooms and neighborhoods.

In addition, Tribes training allowed GECO to build a women-led network of educators from San Cristóbal and Isabela.

The training also promoted what social marketing refers to as social diffusion (McKenzie-Mohr et al.2011). One of the most common reasons people adopt a new behavior is that others close to them have done so. Thus it is critical to increase the visibility of solutions within the community. Most participants in the Tribes workshop were also heads of households and activists with influence over other women and youth groups in San Cristóbal and Isabela. As a result, each workshop participant became a potential amplifier of the plastics-free message.

CLUB ALIVE

Club ALIVE, whose Spanish acronym stands for “Teenagers with Intentions of Ecological Living,” is a youth group whose members have participated in many GECO initiatives. Ashleigh Klingman started Club ALIVE in 2012, and Daniela Chalén strengthened the group in 2017.

Among other activities, Club ALIVE has revived the Comparsa Galapagos, a puppet troupe comprised of six giant puppets that tour different neighborhoods of San Cristóbal, spreading the message of responsible use of plastics. Club members learned puppetry techniques and launched a play called “Once upon a time without plastics,” which invites audiences to reflect on their consumption habits and their responsibility for keeping the Islands clean. To reinforce its message about responsible consumption, Club ALIVE used recycled materials to build many of the musical instruments used in the performances.

Figure 4. Club ALIVE and GECO launch a play using giant puppets in the streets of San Cristóbal. Photo: José Guerrero

Through artistic expression in public spaces, Comparsa Galapagos has succeeded in increasing the visibility of messages about plastics. The initiative also reflects the commitment of its young participants to change their own behavior. Daniela Chalén and other GECO collaborators have encouraged female leadership within Club ALIVE, promoting shared decision-making and reversing longstanding cultural norms under which leadership roles have generally been held by men.

REDUCING SOCIAL ACCEPTANCE OF PLASTIC

We seek to reduce the social acceptance of plastics through workshops focused on children and the general public. We have conducted approximately 100 workshops in local primary schools and high schools, and we have shared our message with 3,000 residents during more than 30 public events in San Cristóbal.

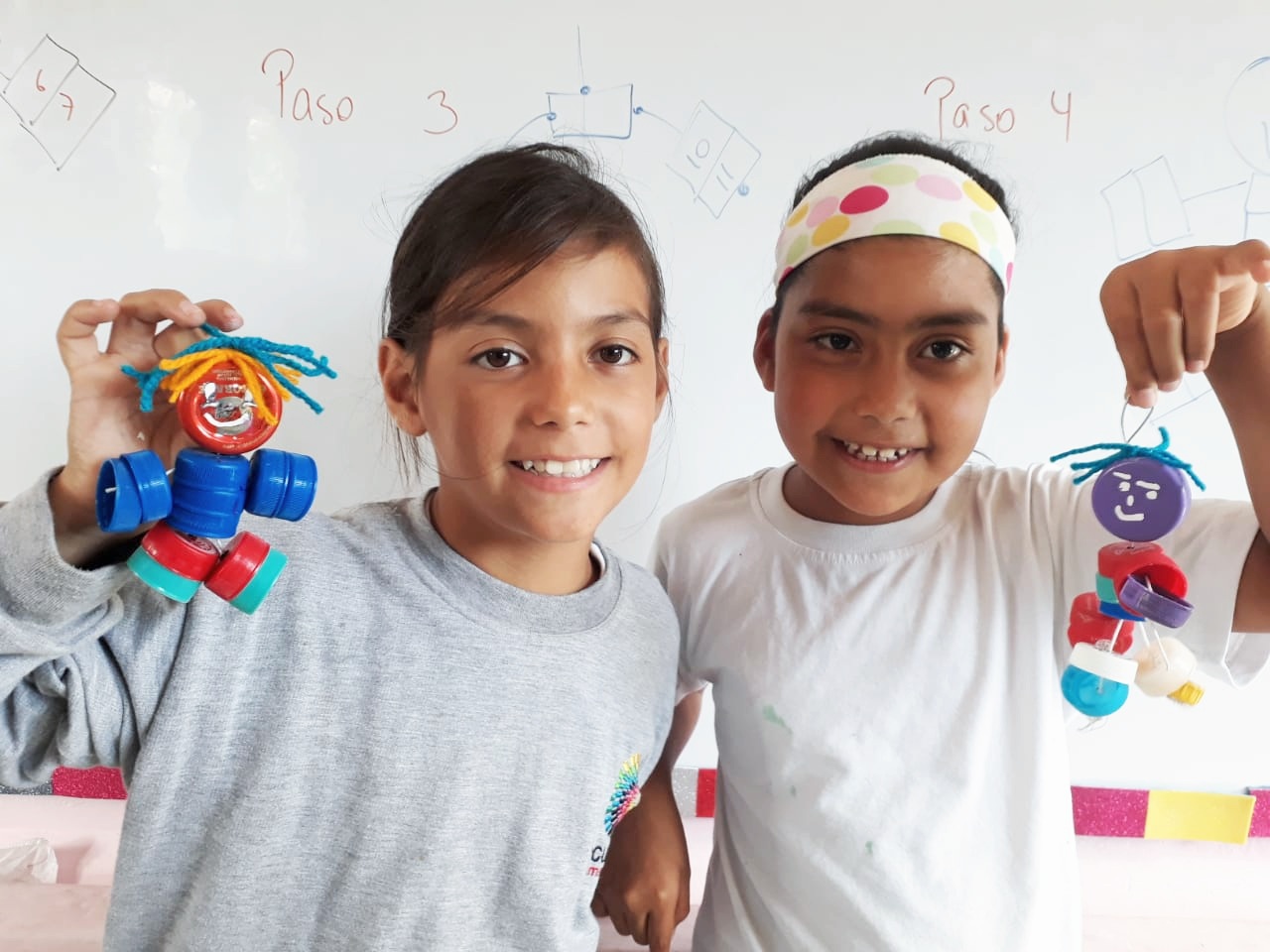

Figure 5. San Cristóbal students participate in educational workshops with Tapín dolls. Photo: Carolina Velasteguí

Along the way we created a doll named “Tapín,” which has become the unofficial mascot of our campaign. During workshops, nearly 400 students have made Tapín dolls from plastic bottle caps or “tapas.” Leidy Apolo has coordinated student collection of more than 9,000 pieces of plastic material on beaches and in urban areas of San Cristóbal. As part of the process, students recorded the number of plastic caps collected and the sites where they found them, thereby also helping to document the amount of plastic found in different areas of San Cristóbal.

At the end of each workshop, we asked a sample of participating students to complete a questionnaire about their use of single-use plastic bags versus reusable bags in stores and restaurants. In this way, we sought to monitor their progress towards desired changes in behavior. We found that following workshops during which students created Tapín dolls, 95% of participants maintained their commitment to stop using single-use plastics.

OFFERING ALTERNATIVES TO PLASTIC: WHERE THE RUBBER HITS THE ROAD

To successfully transition to a plastic-free culture, it is necessary to provide consumers with practical and accessible alternatives. We have found that reusable cloth bags and aluminum water bottles are the most accepted solutions.

To promote these alternatives, Daniela Chalén and Leidy Apolo visited shops, restaurants and hotels, and they conducted interviews on several local radio stations. Meanwhile, Carolina Velasteguí designed posters and flyers using images of local women who are committed to responsible consumption. These materials were distributed to businesses and via social networks. We produced about 70 publications and delivered 20 communication pieces to local businesses.

As a result of Daniela, Leidy and Carolina’s efforts, by late 2018 eighteen restaurants and several street vendors had adopted sustainable alternatives, such as packaging made of paper and sugar cane byproducts. In some cases, stores decided to eliminate disposable bags completely and require customers to bring their own bags.

LESSONS LEARNED

We have learned that empowering social groups to address environmental issues is a long-term process that requires the collaboration of various actors from civil society and the public sector. Reducing the social acceptance of plastics requires developing messages aimed at specific target groups. In our case we have focused on women as agents of change, along with key actors in primary and secondary schools and local businesses.

We have seen that sharing best practices and positive examples of people who already demonstrate the desired behavior is more impactful than simply talking about the negative effects of plastic. Strengthening the capacity and visibility of groups like Club ALIVE can inspire and motivate change in other members of the community.

In the absence of practical, inexpensive, and readily-available alternatives to plastics, people will always choose the most convenient option. Alternatives must be well suited to the needs of consumers. We recommend establishing more linkages with suppliers of alternative products and strengthening public policy through economic incentives, such as taxes on single-use plastics.

Beyond supporting behavioral change, is important that institutions such as local municipalities and the Governing Council of Galapagos strengthen efforts to eliminate the entry of plastic products into the Islands in the first place. Such efforts should appeal to the social and environmental responsibility of distributors of plastic products on the mainland.

Our strategy of empowering women and young people to address environmental problems demonstrates the potential of Galapagos civil society as an agent of sociocultural change. Galapagos is recognized worldwide for its unique biodiversity. For those of us who live here, this is an excellent opportunity to prove that local communities can promote cultural change based on greater awareness of the fragile place we call home.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Galapagos Conservancy and the Galapagos Conservation Trust for their technical and financial support for this program. We are also grateful to the Governing Council of Galapagos for its active role in promoting the responsible use of plastics. We would like to recognize the following women and men who have shared their hard work and creativity with GECO: Olga, Ricardo, Yesmina, José Jara, Claudio, Steffi, David Torres, La Rana Sabia, Álvaro Rosero, Leíto, Jessica, Picachu, Jorge Alvear, Jared, Luis Fernando, Mayerlin, Juan Esteban, Katty, Carlos Klinger y Angela. Thanks also to the families, children, husbands and relatives who have supported our efforts in different ways, since the time we invest in working towards deep social change in San Cristobal often represents a sacrifice for our families.

REFERENCES

Auta HS, Emenike CU & SH Fauziah. 2017. Distribution and importance of microplastics in the marine environment: a review of the sources, fate, effects, and potential solutions. Environment International 102: 165-176.

Gall SC & RC Thompson. 2015. The impact of debris on marine life. Marine Pollution Bulletin 92(1-2): 170-179.

McKenzie-Mohr D, Lee NR, Kotler P & PW Schultz. 2011. Social marketing to protect the environment: What works. Sage Publications.

Rochman CM, Cook AM & AA Koelmans. 2016. Plastic debris and policy: Using current scientific understanding to invoke positive change. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 35(7): 1617-1626.

Women Engage for a Common Future. 2017. Plastics, Gender and the Environment. Findings of a literature study on the lifecycle of plastics and its impacts on women and men, from production to litter.