Nicolás Moity[1], Juan Carlos Izurieta[2], Eddy Araujo[3], María Casafont[4]

[1]Charles Darwin Research Station, Charles Darwin Foundation, [2]Galapagos Tourism Observatory, Ministry of Tourism, [3]Galapagos National Park Directorate, [4]WWF-Ecuador

Figure 1. Green turtle surrounded by Pacific creolefish at Daphne Menor. Photo: Nicolas Moity/Charles Darwin Foundation

Galapagos is known for its evolutionary processes, high levels of conservation, and a marine reserve that provides unparalleled opportunities for observing wildlife. Many visitors want to experience – at least once – the sensation of weightlessness as they dive with penguins, tunas, barracudas, sea lions, rays, turtles, marine iguanas and especially the hammerhead shark, which has become the symbol of the Galapagos Marine Reserve. As dive tourists suit up aboard their boat, they listen attentively to instructions from their guides. Nevertheless, some chase after turtles to take a selfie. Others get too close to whitetip reef sharks, and many are unaware that their movements are damaging the few corals that survived the 1982-1983 El Niño (Glynn et al. 1988).

Each year approximately 18,000 visitors participate in a dive tour during their stay in Galapagos. Until recently, however, the underwater behavior and ecological footprint of these tourists have been invisible to managers.

As lovers of marine life who have visited other protected areas of the world, we began to ask ourselves about the impacts of diving in Galapagos. Diving allows one to observe what is for many an unknown world. Unfortunately, diving can also cause negative impacts and loss of biodiversity, as documented in studies in the Red Sea (Hannak et al.2011; Zakai and Chadwick-Furman 2002) and the Caribbean (Lyons et al.2015; Tratalos and Austin 2001).

Figure 2.Diver surrounded by Pacific creolefish at Darwin’s Arch. Photo: Nicolas Moity/Charles Darwin Foundation

How can we ensure that dive tourism doesn’t cause negative impacts to the marine environment? As researchers we have taken a first step in responding to this and other important questions by creating DiveStat, an innovative dive tourism monitoring program for Galapagos.

OBSERVING DIVER BEHAVIOR

On land, it’s relatively easy to notice impacts of human activities, such as endemic plants trampled by tourists leaving a trail. It is also easier to control these impacts on land, because peers help to correct bad behaviors like tourists getting too close to animals or using flash when taking photographs.

The marine environment presents greater challenges. The time we can remain underwater is very limited. Our vision is reduced, there are no trails to follow, and it is easy to lose one’s orientation. Our ability to communicate is practically non-existent, and the number of people who can help control underwater activity is limited to the dive guides.

Figure 3. Diver taking photographs of a marine iguana feeding in shallow water at Cabo Douglas, Fernandina Island. Photo: Nicolas Moity/Charles Darwin Foundation

Since 2012, dive centers in Galapagos have allowed our team to accompany dive tours as anonymous tourists. We follow each group of divers, recording data about their underwater behavior without the divers knowing that we are taking notes. We document all that they do: whether they touch or grab onto an organism; the part of their bodies or equipment that makes contact with corals, and if that contact has an appreciable impact (for example, if a piece of coral breaks off); whether they get too close to emblematic species, such as turtles or sharks. We record all observations on tablets made for writing underwater. Using a coding system, we are able to register a lot of information in very little space.

After conducting about 200 such monitoring dives at sites visited by Santa Cruz dive operators, we concluded that eight out of ten divers make contact with the ocean floor during their dive. Fortunately, the impacts are generally minor. In half of these situations contact is with rocks or algae. However, 12% of these incidents involve contact with coral. This figure is significant considering that coral is not abundant in Galapagos, especially in the central islands.

Figure 4. A monitor records diving conditions at the Bajo Gardner dive site, Española Island. Photo: Sofia Green/Charles Darwin Foundation

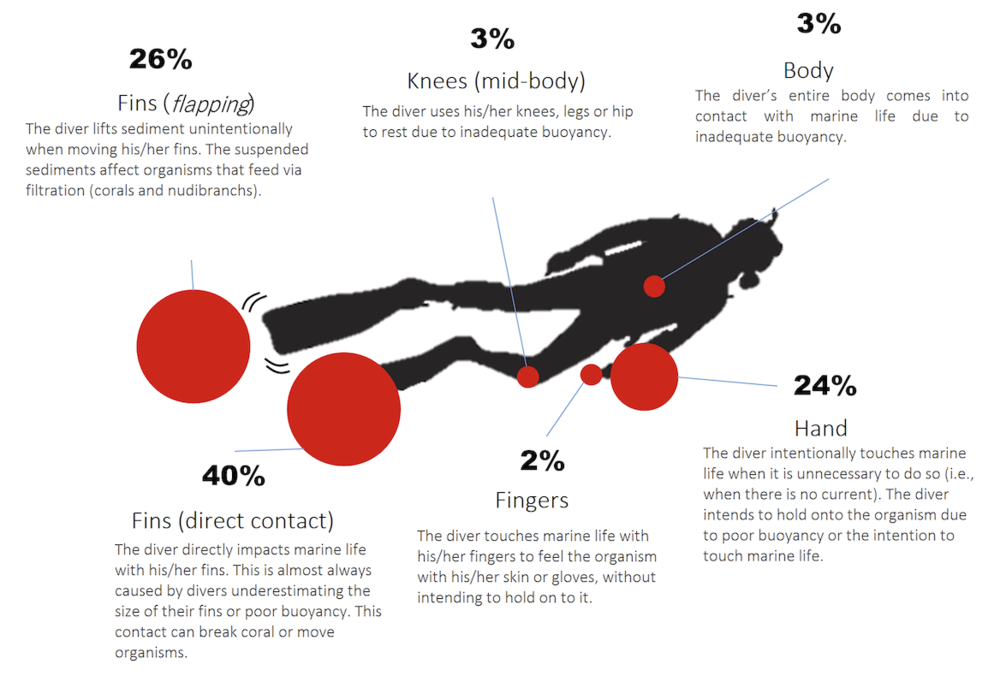

The data collected by our observers reveal that almost all contact is made with scuba fins and hands (Figure 5). About 70% of contact—direct or indirect—is caused by divers flapping their fins. Indirect contact, also known as flapping, occurs when divers raise sediment by swimming too close to the ocean floor, like cars raising dust on a dirt road. This sediment often settles on filtering and photosynthesizing organisms that cannot feed while they are covered.

Figure 5. What sort of contact do divers make with marine life and substrate? Percentages relative to the number of contacts by each part of the body and dive equipment. Source: Underwater monitoring by the DiveStat project.

COLLECTING TOURIST PROFILES

When divers exit the water, we tell them that we are conducting a study to ensure the sustainability of dive operations in the Galapagos Marine Reserve, and we ask them to help by completing a survey. The survey is organized into different sections that together help us to maintain a count of dive tourists in the Islands and to develop profiles of different visitor groups, understand their beliefs about diving and their own behavior, estimate their levels of satisfaction, and identify safety issues. While underwater we identify each diver so that we can compare their behavior with their responses on the survey, in order to try to detect patterns associated with different demographic profiles.

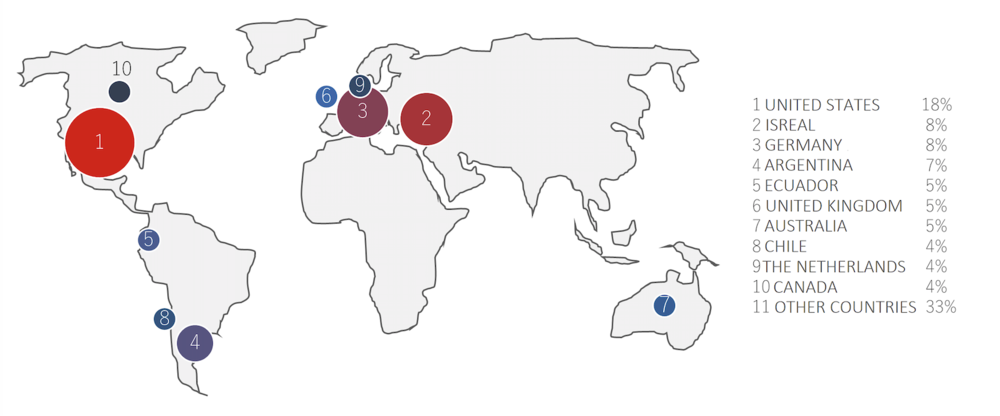

After conducting 1,200 surveys, we have a much better understanding of this segment of the Galapagos tourism sector. Ten countries, half of which are in the northern hemisphere, represent 67% of the dive tourism market. The United States leads this list (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Top countries of origin of divers participating in day dive tour in Galapagos. Source: DiveStat surveys.

Most divers are not very experienced. They tend to have low-level diving certifications and have made an average of 13 dives prior to diving in Galapagos.

Based on our observations of diver behavior and divers’ responses when asked if they were aware of having caused impacts, we determined that 64% of contacts are unintentional and that 91% of divers are unaware that they are leaving an underwater footprint. We believe that these impacts could be minimized if divers learn to better control their bodies and their diving equipment. Dive guides could help by emphasizing the importance of being aware of one’s body during pre-dive briefings, and by explaining the damage divers can cause to fauna and the seafloor.

CITIZEN SCIENCE

DiveStat also invites tourists to participate in the monitoring of megafauna species that they observe during their dives, thus incorporating an element of citizen science. Citizen science programs are widely recognized as simple alternatives to conventional scientific biodiversity monitoring (Silvertown 2009), and they can result in the collection of a lot of data at very low cost. In the case of DiveStat, citizen science also raises environmental consciousness among visitors to Galapagos, by involving them in a local conservation activity.

To date, tourists have reported approximately 7,000 sightings of 15 different species, primarily sharks, turtles, rays, mantas and sea lions. These data increase our understanding of the natural variability of species at visitor sites, and over time, they will help us to recognize changes in population size and distribution. We are still in the process of creating databases to manage these data, but we plan to compare observations reported by tourists with more robust data on species distribution and abundance to help identify patterns.

SHARING RESULTS WITH THE PUBLIC

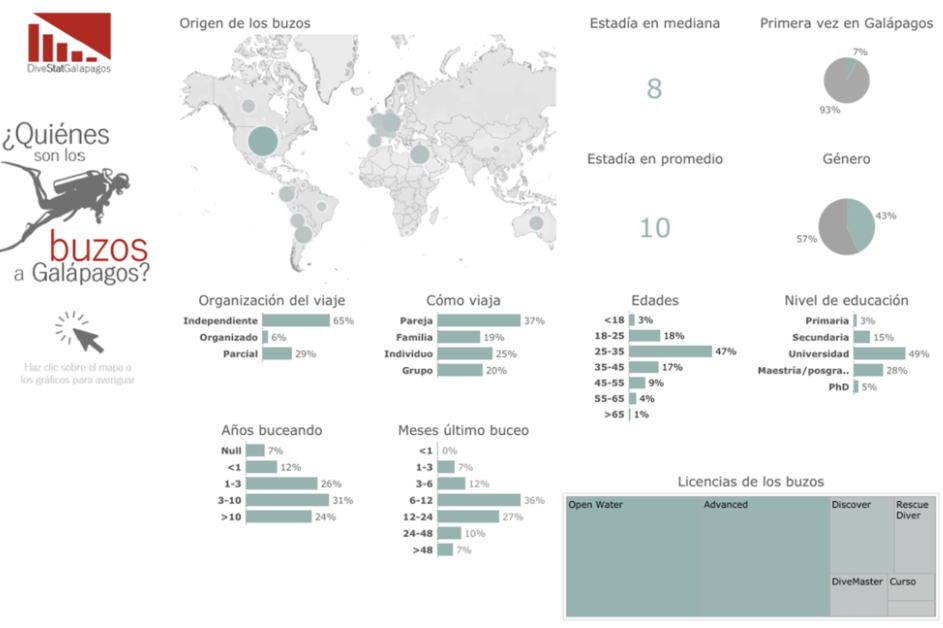

The results of Divestat are published on the website http://www.observatoriogalapagos.gob.ec/divestat in formats that are easily understood by the general public, dive operators and conservation decision-makers. Users can customize data presentation to view results relevant to their specific interests (Figures 7 and 8).

For example, to view the profile of dive tourists from the United States, you can click on the map of the U.S., and relevant results appear automatically. The same is the case for all other data fields. Each dive agency is provided private access to data so that it can better understand its clientele.

Figure 7. Screenshot of on-line data that describes the characteristics of diving trips in Galapagos.

Source: Galapagos Tourism Observatory website: https://www.observatoriogalapagos.gob.ec/divestat

Figure 8. Screenshot of species observation data at dive sites accessible from Santa Cruz Island. Source: Galapagos Tourism Observatory website: https://www.observatoriogalapagos.gob.ec/divestat.

Wildlife observation data collected by citizen scientists can be viewed by both species and dive site. This information can be used by dive agencies to inform their clients about the presence of species of interest at lesser-known dive sites.

Perhaps the most important aspect of these data is that they can be used by the Galapagos National Park Directorate and the Ministry of Tourism to make informed management decisions. For example, DiveStat has helped to identify training needs for dive guides, which we have subsequently addressed through safety workshops and sharing of best practices. DiveStat results have been included in the official courses required for Naturalist and Adventure Guides certification by the Galapagos National Park Directorate.

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

This project incorporates technology in innovative ways and reduces the time between data collection, analysis and publication of results. It also involves local tour operators and engages tourists as citizen scientists helping to monitor marine megafauna. The end goal is to ensure that the dive tourism is sustainable, responsible, and compatible with the delicate marine ecosystems of Galapagos.

DiveStat is a multi-institutional project that involves the Galapagos National Park Directorate, the Charles Darwin Foundation, the Ministry of Tourism, World Wildlife Fund-Ecuador and dive tourism operators. It is also a multi-disciplinary project that collects both ecological information, such as the impacts of diving on marine biodiversity, as well as social information, such as demographic profiles of dive tourists, tourist attitudes and visitor satisfaction. In this way DiveStat is helping us to develop a holistic understanding of the dive tourism sector.

We recommend that DiveStat data collection continue and that funding be secured to ensure the program’s sustainability. In the future we would like to study whether small changes in the way dive tourism is managed could significantly improve the underwater behavior of divers. For example, we are developing a short video that we hope will help guides to present more effective pre-dive briefings. This strategy has proven effective in other parts of the world.

We would also like to assess the medium- and long-term impacts of diving on biodiversity at different dive sites. To do so, we hope to monitor dive sites with different levels of visitor traffic (high and low) and compare our observations with those made at sites with similar ecological conditions that are not visited by dive tourists (control sites). We will focus on sessile species on the ocean floor, like corals, and vertebrates like sharks, rays, turtles and sea lions.

We have seen that diving can cause negative impacts to marine life, and therefore this activity must be monitored and evaluated. Measures such as additional training for dive guides and more effective communication with divers about proper behavior can help ensure that dive tourism doesn’t negatively affect the unique underwater biodiversity and marine ecosystems of Galapagos.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the Charles Darwin Foundation, the Galapagos National Park Directorate, the Ministry of Tourism’s Galapagos Tourism Observatory and WWF-Ecuador for the institutional support provided for implementing this study. We are also grateful for the support of the many volunteers who have collaborated in the project, including (in alphabetical order): Angie Carrión, Marta Díaz, David Flores, María Virginia Gabel, Carla Huete-Stauffer, César Jiménez, Andrea Lema, Lisa Linduz, Elena Pérez, Sofía Trujillo and Felipe Wittmer. The Divestat Galapagos Project was carried out with funds from Ecoventura’s 2015 Galapagos Marine Biodiversity Fund managed by WWF-Ecuador. This publication is contribution number 2236 of the Charles Darwin Foundation for the Galapagos Islands..

REFERENCES

Glynn PW, Cortés-Núñez J, Guzmán-Espinal HM & RH Richmond. 1988. El Niño (1982-83) associated coral mortality and relationship to sea surface temperature deviations in the tropical eastern Pacific. En Proceedings of the 6th International Coral Reef Symposium, Australia. pp. 237–243.

Hannak JS, Kompatscher S, Stachowitsch M & J Herler. 2011. Snorkelling and trampling in shallow-water fringing reefs: Risk assessment and proposed management strategy. J. Environ. Manage. 92: 2723–2733. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.06.012.

Lyons PJ, Arboleda E, Benkwitt CE, Davis B, Gleason M, Howe C, et al. 2015. The effect of recreational SCUBA divers on the structural complexity and benthic assemblage of a Caribbean coral reef. Biodivers. Conserv. 24: 3491–3504.

Silvertown J. 2009. A new dawn for citizen science. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24: 467–471.

Tratalos JA & TJ Austin. 2001. Impacts of recreational SCUBA diving on coral communities of the Caribbean island of Grand Cayman. Biol. Conserv. 102: 67–75. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00085-4.

Zakai D & NE Chadwick-Furman. 2002. Impacts of intensive recreational diving on reef corals at Eilat, northern Red Sea. Biol. Conserv. 105: 179–187. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00181-1.

International. Puerto Ayora, Galápagos, Ecuador. 66 pp.