Erika Guerrero, Manuel Mejía, Ronal Azuero, Viviana Duque, José Loaiza, Marco Echeverría, Nancy Durán, Emilio Armas, Joselito Mora and Marilyn Cruz

Agency for the Regulation and Control of Biosecurity and Quarantine for Galapagos

Figure 1. The Argentine ant, one of the most invasive species in the world. Photo: Phil Lester

In the Galapagos Islands, some of the greatest impacts to native fauna are caused by organisms smaller than a seed – ants. There are three species of invasive ants in the Archipelago: the tropical fire ant (Solenopsis geminata), the small fire ant (Wasmannia auropunctata) and the big-headed ant (Pheidole megacephala). These species can infect the eyes of giant tortoises and eat their young, harm baby birds, and even kill small animals by attacking them in groups. Birds and tortoises are not their only victims; in agricultural zones, ants inflict severe bites on farmers and kill young chickens.

In total, 22 species of introduced ants have been reported in Galapagos, compared to one endemic and eight probably endemic species. The big-headed ant and the small fire ant are among the 100 most harmful invasive species in the world.

Invasive ants can quickly establish themselves, reproduce exponentially, and compete with the endemic ant species of the Archipelago. Since its inception, the Agency for the Regulation and Control of Biosecurity and Quarantine for Galapagos (ABG) has focused on combating the entry of new species. In this article we present our three main strategies to prevent ant invasions in Galapagos: comprehensive monitoring, direct control, and education and outreach.

THE ARGENTINE ANT AND THE ORIGINS OF OUR SYSTEM

In 2014 ABG technicians detected the Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) on a plane that arrived on Baltra Island. Like the ant species mentioned above, the Argentine ant is considered one of the most dangerous and invasive species in the world. It is native to the Paraná River Basin, and is found in northern Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay, as well as in southern Brazil and Bolivia. This species has already invaded mainland Ecuador.

On oceanic islands such as Galapagos, the arrival of the Argentine ant could generate a symbiotic relationship with aphids and scale insects, which secrete sugary substances eaten by ants. In return, ants protect these species from predators and parasitoids. Scale insects and aphids damage vegetation, so increases in their populations due to the Argentine ant could pose a significant threat to the Galapagos agricultural sector. The Argentine ant can also cause health problems because it is a vector for pathogenic microorganisms.

Alerted to the Argentine ant’s arrival, ABG carried out our first rigorous, ant-centric monitoring and control efforts. We activated a monitoring system on all populated islands and at departure points in Quito and Guayaquil. We determined that the Argentine ant was not present in Galapagos, but we discovered abundant populations in Mariscal Sucre International Airport in Quito. Since this time, we have maintained a strict monitoring and control system at the Quito airport, with specific attention to cargo holds.

COMPREHENSIVE MONITORING: PREVENTION TO PROTECT GALAPAGOS

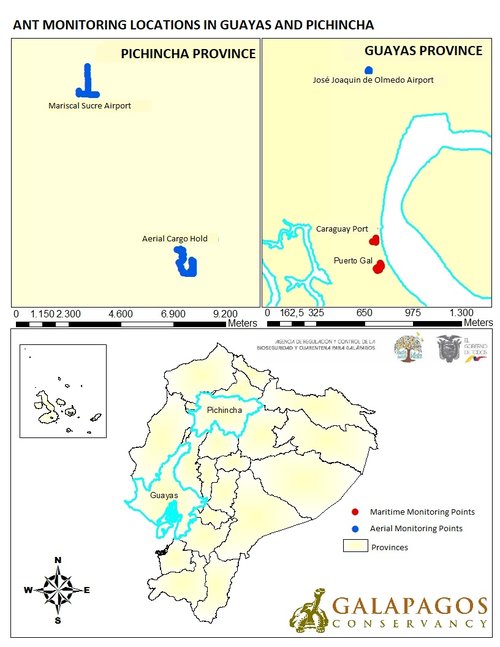

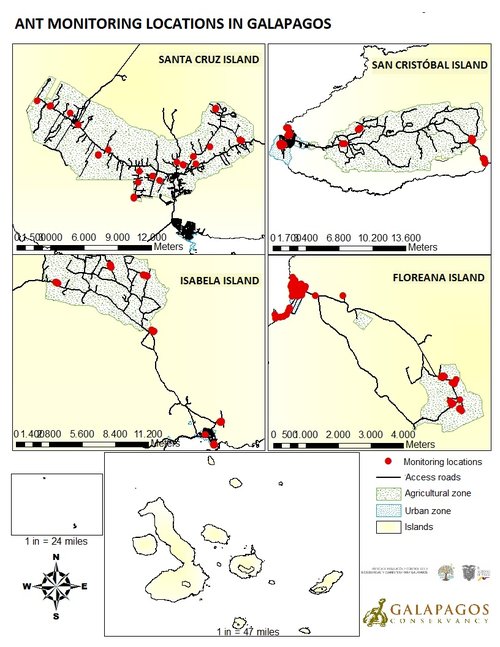

In 2017 we intensified monitoring in Quito and Guayaquil, as well as in the urban and rural areas of Santa Cruz, San Cristobal, Isabela and Floreana (Figure 2a and 2b). To attract and detect ants, we use baits made from tuna, honey and sausage (Figure 3). After collecting the ants (Figure 4), we label samples and deliver them to the ABG Entomology Laboratory for identification.

Figure 2a. Ant monitoring sites in mainland Ecuador and in the populated islands of Galapagos.

Figure 2b. Ant monitoring sites in mainland Ecuador and in the populated islands of Galapagos.

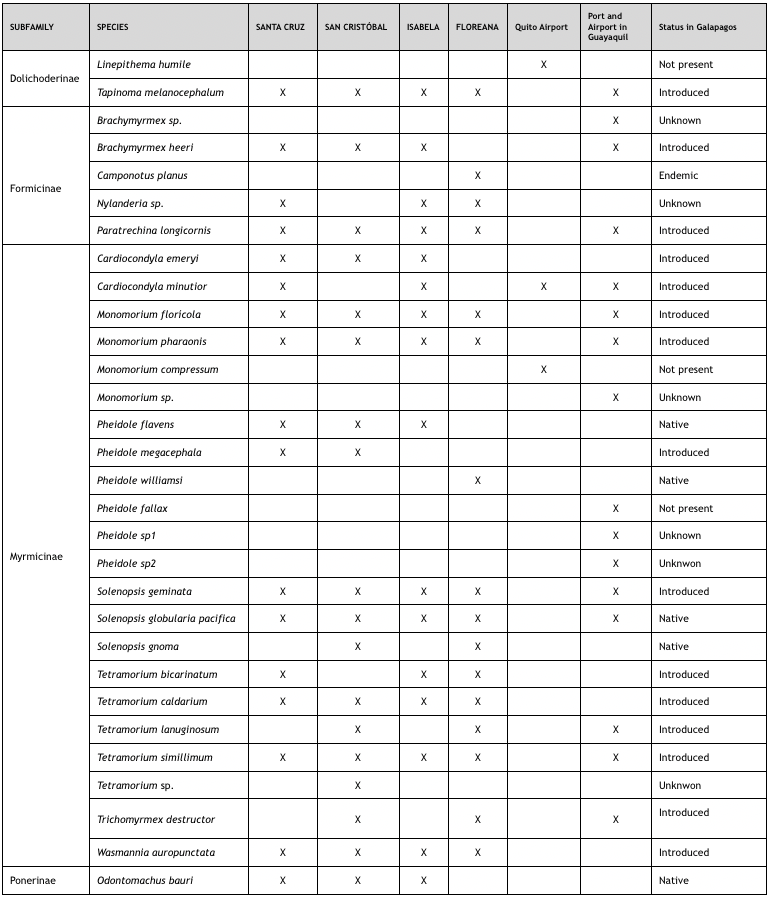

In 2017, we analyzed approximately 4,000 samples representing 25 different species of ants (Table 1). We did not detect any new species. We monitored a total of 53 locations: 14 on mainland Ecuador, 16 on Santa Cruz, nine each on San Cristóbal and Isabela, and five on Floreana.

Thanks to these monitoring efforts, we now have a better understanding of the ant species present both in the Islands and at departure points in mainland Ecuador. The most frequently detected ants in Galapagos were the small fire ant and tropical fire ant, as well as five introduced but non-invasive species. Although another invasive species, the big-headed ant, was not detected often in the Islands, it was one of the most commonly detected species in Quito and Guayaquil.

Figure 3. Positioning of sausage, honey and tuna baits. We position three different types of bait in close proximity to each other because different species of ants are attracted to different foods. Photo: ABG Archives

Figure 4. Samples of ants collected in a honey bait. The number of ants within a sample is relative: it depends on the population of ants. Sometimes baits do not attract any ants, and sometimes they fill up. Photos: ABG Archives

DIRECT CONTROL: BATTLING INTRODUCTIONS

We complement our monitoring efforts with direct control measures. When a plane lands in Galapagos, we confirm its compliance with disinfection procedures at the Quito and Guayaquil airports. This activity is carried out every time an aircraft travels to the Islands. For the last two years we have also disinfected cargo travelling to Galapagos. In 2017, we applied Gastoxin fumigation tablets to 166 cargo containers at the PuertoGAL dock in Guayaquil.

Within Galapagos, we conduct fumigations upon homeowners’ requests. We performed 30 home fumigations in 2017.

EDUCATION AND OUTREACH

All ABG checkpoints in Galapagos and on the mainland have a reference collection of ants so that technical personnel in each office can easily identify high-risk species. We have also developed a Catalogue for the Detection and Identification of Ants, which serves as an additional tool for ABG technicians and inspectors.

To disseminate the results of our work, we conduct workshops for technicians from other institutions and for agricultural producers from Floreana, Isabela, Santa Cruz and San Cristóbal Islands. During the workshops we ensure the audiences are familiar with the species of ants found in Galapagos, their distribution and potential impacts. We also highlight those species that pose the highest risk of entry from Quito and Guayaquil.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Comprehensive monitoring at the airports in Quito and Guayaquil has allowed us to detect very aggressive species such as the Argentine ant, and to carry out direct control measures so that this and other species do not reach Galapagos.

The frequency of arrival of ants via maritime and air transport continues to grow. It is essential to sustain the existing monitoring system to detect the arrival of any new organism in Galapagos in a timely fashion. Continued financial resources are needed for these important activities.

We also seek to continually update the skills of our technicians and inspectors. Professional development efforts for ABG staff should be complemented by outreach to the public, with the goal of explaining the potential impacts of invasive ants on populated islands, both for ants that are already present in Galapagos and for those species with the highest risk of arrival.

We would like to implement a rapid communication system to allow agricultural producers to inform ABG of any suspected new species of ant found in their crops.

It is up to all of us to be careful about what we bring to Galapagos and to ensure that the Islands remain free of new invasive species. If you see any new arrival, or are unsure about a species you observe, report it immediately to the ABG!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Galapagos Conservancy for its collaboration in the implementation of this study to prevent the entry of ants that could pose serious problems for the Galapagos Islands.

Table 1. List of species collected during monitoring activities in the populated islands of Galapagos and at the Mariscal Sucre (Quito) and José Joaquín de Olmedo (Guayaquil) airports, the Caraguay pier and PuertoGal. (An “X” indicates the presence of the species at that location.) Source: ABG Entomology Laboratory, 2017.