Paulina Couenberg, René Ramírez, Sandra García, Rodrigo Paredes, Hernán Simbaña, Jimmy Bolaños

Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock, Galapagos District Directorate

Figure 1. Waste collection in a rural area. Photo: Carolina Peñafiel

Concentrated on the Archipelago’s oldest and most populated islands, the humid zones of Galapagos were originally covered by forests of Scalesia pendunculata and Miconia robinsoníana, forming unique ecosystems very different from those in lower elevation areas (Figure 2). Little by little, these forests have been replaced with crops and pastures, since the humid conditions of the highlands are well-suited for agriculture and livestock production. Nevertheless, the highlands still possess areas of high ecological value that provide essential environmental services, such as the open and underground aquifers that capture and filter rainwater for human consumption, livestock and irrigation.

To avoid contamination of these sources of freshwater, it is essential that we properly manage plastic garbage, agrochemical residues, and other inorganic waste generated by the agricultural sector. However, rural waste management has been problematic in the Islands. Our team in the Galapagos District Office of the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (also known as MAG, for its acronym in Spanish) identified the need to help preserve highland ecosystems by organizing an inter-institutional “minga”, or voluntary work brigade. Over the course of two days in 2018, we collected more than 24,000 kilograms of inorganic waste, much of which had been accumulating on farms for several years. The minga allowed us to assess current waste management challenges in the agricultural zone, and to promote solutions.

Figure 2. A forest of Miconia robinsoníana in the protected area at Media Luna, Isla Santa Cruz. Photo: Paulina Couenberg

THE CLEAN FIELDS MINGA

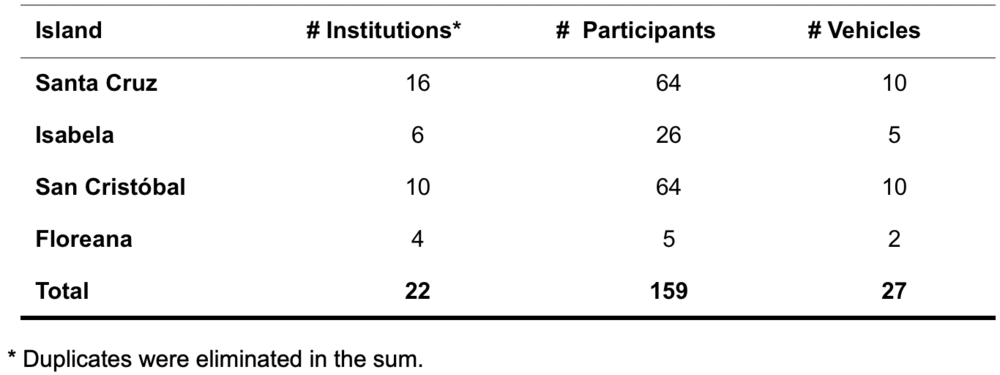

We organized the Clean Fields Minga during the last week of July 2018 with the help of staff from 11 public institutions, seven non-governmental organizations and four private sector groups (Table 1). In the days leading up to the minga, we held meetings in rural communities to encourage farmer participation, and we distributed flyers through social media networks (Figure 3). As a result of these efforts, 240 farmers collected waste on their farms and left it by the roadside for collection.

Table 1. Participants in the Clean Fields Minga.

Figure 3. The promotional flyer circulated via social networks.

During the two days of the minga, we formed work brigades comprised of four to five people each. These groups traveled to different rural areas on Santa Cruz, San Cristóbal, Isabela and Floreana Islands by truck or van to collect waste gathered by farmers and take it to the local recycling center to be weighed and sorted (Figure 4). In each group, a representative from the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock recorded the quantity of agrochemical containers and the weight of plastics, glass, scrap metal and other types of waste.

Figure 4. Volunteers unload waste at a recycling center. Photo: Carolina Peñafiel

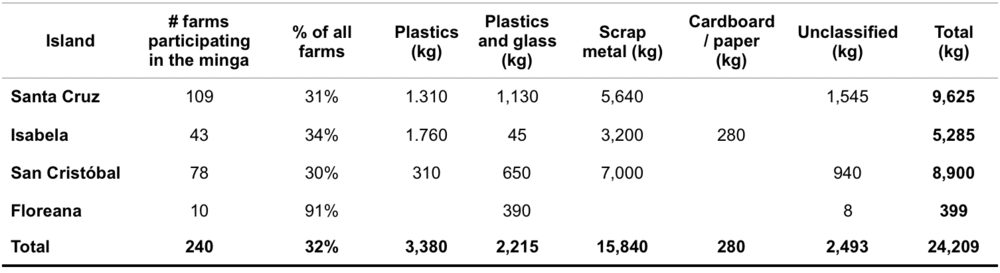

Across all islands, we collected a total of 3,380 kg of plastic waste, 280 kg of cardboard, 2,215 kg of plastic and glass, 2,493 kg of unsorted waste and 15,840 kg of scrap metal from 240 different farms, representing 32% of all farms in the Archipelago (Table 2).

Table 2. Waste collected by type.

The significant amount of waste collected suggests that the minga had an important impact on the agriculture sector. Patricia Ortiz, a farmer on Santa Cruz Island, urged other community members carry out proper sorting and recycling practices: “Agricultural waste affects animals and crops; we need to be conscious of the fact that we live in a unique part of the world.”

Unfortunately, the minga confirmed that waste collection in the agricultural zone is inadequate. Even though the municipal government on each island collects waste classified into organics, recyclables and non-recyclables, most farmers did not sort the waste from their farms. Additionally, collection schedules tend to be irregular in rural areas, and many farmers are unfamiliar with collection days and routes. Moreover, a number of farms are located far from collection routes. As a result, many farmers accumulate or burn plastics, glass, scrap metal, and other waste on their farms.

During the minga we collected a total of 1,622 agrochemical containers (Figure 5), which suggests to us a high risk of environmental contamination from herbicides and pesticides. The 2014 Galapagos Agricultural Census indicated that more than half of discarded agrochemical containers are improperly handled. Our minga revealed that most farmers leave such waste out in the open. This practice can allow the residual agrochemicals and veterinary medicines left in discarded plastic containers, glass vials and aluminum-lined plastic bags to seep directly into sources of freshwater.

Figure 5. Agrochemical containers collected during the Clean Fields Minga.

COLLABORATIVE EFFORTS TO IMPROVE WASTE MANAGEMENT

Based on what we learned during the minga, the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (MAG) has begun working with a number of institutions to improve agricultural waste management and to strengthen farmers’ understanding of this issue.

In conjunction with municipal governments, MAG is developing workshops and education materials to train farmers in the proper management and classification of inorganic farm waste. We are also planning to launch a regular rural waste collection service, and to inform farmers about collection schedules and routes.

MAG will also collaborate with the Galapagos Biosecurity Agency to train farmers in proper management of agrochemical containers via a practice known as “triple rinsing”. This process involves draining any remaining chemicals from containers into the tank of backpack sprayers or other application equipment, then rinsing the container with fresh water a minimum of three times, and then returning the contaminated water to the application tank to avoid pollution of the environment.

Figure 6. Participants in the minga on San Cristóbal (left), Isabela (right) and Santa Cruz (top). Photos: Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (San Cristóbal and Isabela) y Carolina Peñafiel (Santa Cruz)

We also plan to work with farmers to coordinate collection of empty agrochemical containers and agrochemicals that have passed their expiration date. To do so, we will need to establish a collection center on each island to facilitate the return of containers to manufacturers on the Ecuadorian mainland. We also want to make sure that Galapagos agrochemical distributors inform farmers that they must return empty agrochemical containers. Indeed, existing law requires that agrochemical containers be returned to the site of purchase.

Finally, in partnership with Conservation International-Ecuador, MAG is implementing a program called Conservation Agreements, which promotes an innovative model of sustainable agriculture. Farmers who participate in the program agree to support conservation of soil, water, and endemic and native species via implementation of sustainable practices, including proper management of inorganic waste. In exchange for farmers’ commitment, the program offers workshops, educational materials, ongoing technical assistance, and access to farm equipment, seeds and credit. This program was piloted in Santa Cruz beginning in November 2018 and will be expanded to other populated islands.

MINGAS AS A CONSERVATION TOOL

Public and private organizations have organized coastal cleanups to protect the Galapagos Marine Reserve for a number of years. These events are very popular and involve many members of the Galapagos community. For example, the Galapagos National Park Directorate’s 2018-2024 Integrated Plan for Coastal Cleanups has already collected 22 tons of garbage from 13 islands. As part of this plan, the National Park is implementing a campaign known as “More Life, Less Trash,” which encourages the use of reusable water bottles in schools to reduce single-use plastic bottles in Galapagos.

Prior to our project, however, cleanup efforts had never focused on populated urban or rural areas. The Clean Fields Minga is a tool that can help us to better understand the challenges related to inorganic waste management in agricultural areas, and that can be replicated at regular intervals. We are already planning a second Clean Fields Minga for 2019.

We are also working to link the mingas with the agrochemical waste collection program of the APCSA, an association of Ecuador’s leading producers and importers of agrochemicals. Through this alliance, we hope to establish collection centers in each community to facilitate the return of empty agrochemical containers to the mainland for their proper disposal. This will allow us to advance Ecuador’s National Plan for Integrated Management of Plastic Agricultural Waste, and to contribute to a Galapagos free of single-use plastic containers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

MAG-Galapagos would like to thank the many farmers and volunteers who participated in the Clean Fields Minga, including: Farmers from Santa Cruz, San Cristóbal, Isabela and Floreana, the Galapagos National Park Directorate, the Galapagos Biosecurity Agency, the Galapagos Governing Council, the Ecuadorian Navy, the National Police, the Municipal Government of Santa Cruz, the Fire Department, the Parish Governments of Bellavista, El Progreso, Tomás de Berlanga and Santa Maria, the District Office of the Ministry of Health, the Charles Darwin Foundation, Frente Insular de la Reserva Marina Galápagos, Conservation International-Ecuador, Galapagos Conservancy, Island Conservation, World Wildlife Fund, Intercultural Outreach Initiative, Hacienda La Tranquila, Galapagos Experience, Floreana Verde Farmer’s Association, and Lindblad Expeditions- National Geographic Fund.