Heinke Jäger[1], Claudio Crespo[1], Francisco Abad[2], Alizon Llerena[2] and Paulina Couenberg[2]

[1]Charles Darwin Research Station, Charles Darwin Foundation, [2]Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock, Galapagos District Directorate

Figure 1. View of the agricultural zone on Santa Cruz Island. Photo: Heinke Jäger

There are now 1,476 non-native species established in the Galapagos Islands, over 90% of which are plants and insects (Toral-Granda et al. 2017). Invasive insects alone cause damages of at least US$70 billion per year to the global economy (Bradshaw et al. 2016), while the economic costs of invasive plants are currently unknown.

In Galapagos, the impact of invasive species on farmers has received far less attention than the risk that invasives pose to the protected ecosystems in the Galapagos National Park (Causton & Sevilla 2008). Yet farmers are key allies in conservation. They keep the ground covered with beneficial plants to displace the invasive ones, and they invest in agrochemicals that ultimately protect both agricultural crops and parts of the native flora.

In 2016, the staff of the Charles Darwin Foundation and the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (MAG, for its initials in Spanish) came together to learn from farmers on Santa Cruz Island. We sought to find out more about which invasive species pose the biggest challenges on agricultural lands, which herbicides and insecticides farmers use, and how they apply them.

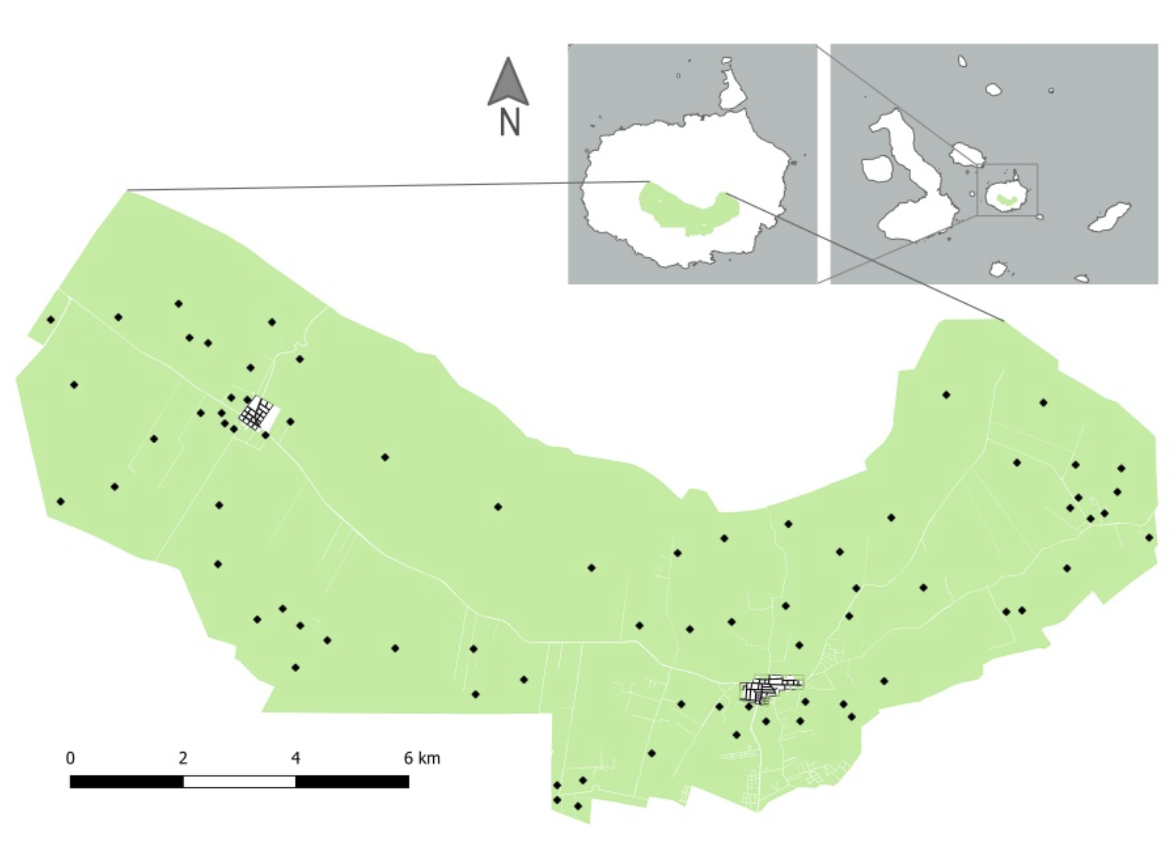

We interviewed farmers in the Santa Rosa, Salasaca, El Occidente, Los Guayabillos, Bellavista, El Camote and Cascajo districts (Figure 2), which together cover 9,592 hectares, or about 100 square kilometers. Farmland in these districts is divided into 357 so-called Agricultural Production Units (APU; CGREG 2014), which are either individual farms or land from different farms combined. We conducted interviews with farmers living in 73 of these APU, which collectively comprised 29% of all agricultural land in Santa Cruz.

Figure 2. Location of the agricultural zone on Santa Cruz Island and of Santa Cruz Island within the Galapagos Archipelago. The 73 interview locations are indicated by black diamonds. Map: Carolina Carrión and Claudio Crespo.

Over the course of about 45 minutes, we asked each farmer a set of standard questions about invasive plants, ants, and their use of herbicides and insecticides. Many interviewees had a long history in Galapagos: about 25% had been living in the Islands for more than 45 years, and nearly 20% were in their 70s and older.

INVASIVE PLANTS

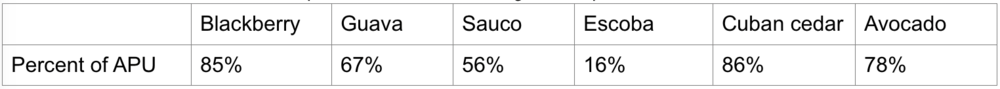

Farmers identified blackberry (Rubus niveus) as the most problematic species on their farms, followed by guava (Psidium guajava), sauco (Cestrum auriculatum) and escoba (Sida rhombifolia) (Table 1; Figure 3). These species provided farmers little or no economic benefit, and 81% of the farmers we interviewed used herbicides to control them. In contrast, farmers usually do not control other common invasive plants that they harvest, such as Cuban cedar (Cedrela odorata) and avocado (Persea americana).

Table 1. Percent of APU where invasive plants were found. APU = agricultural production unit.

The most popular herbicides were Anikil and Combo. Some farmers mixed these two together, likely applying a concentration higher than recommended. We were surprised by the frequent use of Anikil, since this herbicide is not very effective for woody species like blackberry; it is instead best suited for broad-leafed herbs and grasses (Nufarm 2012).

We learned that farmers may be inadvertently creating resistance in invasive plants through repeated applications of the same herbicide at concentrations below those recommended by the manufacturer. For example, of the 28 farmers who controlled blackberry chemically, only five used the recommended concentration for Anikil. Most instead used concentrations that were too low to kill the blackberry plants. They therefore ended up applying the herbicide several times, increasing the total amount used, with plants ultimately building resistance due to repeated exposure.

Herbicides are also mixed with water prior to application, and the pH of the water is key: each herbicide has a different pH optimum, outside of which it is less potent and less likely to kill the plant. However, only 15% of the farmers we interviewed measured the water’s pH before mixing it with the herbicide. Thus sub-optimal pH values could also be necessitating repeated herbicide applications, again building up plants’ resistance.

Figure 3. The four most problematic invasive plants in the agriculture zone of Santa Cruz (clockwise): blackberry, guava, sauco, and escoba. Photos: Heinke Jäger, Conley McMullen, Charles Darwin Foundation archives

INVASIVE ANTS

The highly invasive tropical fire ant (Solenopsis geminata) was the most abundant and problematic insect pest for Santa Cruz farmers (Figure 4). We encountered it in all but one of the 73 Agricultural Production Units (APU) that we sampled. Tropical fire ants commonly caused severe stings to farm workers, especially while they were sowing or harvesting crops (70% of APU) or when ants entered farmers’ homes (71% of APU). Poultry farms reported the most severe impacts. Here, fire ants frequently killed chicks while they were hatching and attacked hatched chicks and adults.

Figure 4. Tropical fire ants swarm a peanut butter stick. Photo: Wilson Cabrera.

To control this pest, most farmers used the insecticides Cyperpac (44% of APU), SiegePro (26%), or Bala 55 (14%). When exposed to the liquid Cyperpac, ants die on the spot, and thus farmers see an immediate result, which may explain their preference for this insecticide. SiegePro, on the other hand, is a granulate that ants pick up and transport to the nest, where it subsequently kills the entire colony. While this process takes longer and is not as visible, SiegePro is actually much more effective than Cyperpac in reducing ant population numbers (Sergio Sanchez, pers. comm.).

Of the farms where the tropical fire ant is currently found, 94% previously hosted the invasive little fire ant (Wasmannia auropunctata). We suspect that the tropical fire ant has replaced the little fire ant over the last 10 years, possibly by outcompeting it.

SAFETY

Many of the farmers we interviewed did not use proper safety procedures during herbicide and insecticide application. Although 85% of interviewees used some kind of protection, this was generally limited to wearing a surgical mask and clothing such as overalls, which are not sufficient. Only 36% of farmers wore gloves when applying agrochemicals.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION

Fifty-three percent of our interviewees asked the agrochemical distributors for advice about the herbicides and insecticides most suitable for controlling invasive species and how to use them. An additional 37% sought guidance from public institutions in Galapagos, primarily the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (MAG), and about 20% had also received training or technical assistance on how to use agrochemicals, again mainly from MAG.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR IMPROVING AGROCHEMICAL CONTROL

Our work suggests that farmers need better training about control of invasive species in the agricultural zone. This is consistent with the results of a previous study by O’Connor and d’Ozouville (2015), yet little action has been taken since their findings were published.

We recommend evening courses to ensure that training reaches the majority of farmers, along with creation of educational videos for those who are unable to attend. Videos should engage local farmers as the main actors and be distributed as a phone App or a DVD.

Agrochemical distributors should also participate in training courses, since more than half of the farmers interviewed sought their advice on recommended herbicide and insecticide application, yet they often ended up using the wrong products.

Based on this study, the Charles Darwin Foundation and MAG have developed a laminated table for farmers that lists the recommended herbicides for controlling the four most problematic plant species (blackberry, guava, sauco, escoba), including recommended herbicide concentrations and application modes. This table will be distributed during meetings of the local farmers’ associations and at the local fruit and vegetable market. We are still developing recommendations for the tropical fire ant, due to the unavailability of SiegePro in Ecuador at the moment.

We suggest development of additional informational materials that explain the risk of creating resistance in invasive plants through repeated applications of the same herbicide at concentrations below those recommended, or by applying herbicides at the wrong pH. These materials should be accompanied by practical supplies, such as pH indicator strips and an easy-to-use cup for measuring the exact amount of agrochemical needed. Indicator strips should come with a list of pH optimums for the mostly commonly used herbicides and insecticides and a description of how to measure pH.

We advocate training courses for MAG staff as well, to advance their knowledge about the use of agrochemicals for the control of invasive species and to ensure provision of consistent advice to farmers.

At the moment, agrochemicals are the only way to effectively control invasive species at large scales in Galapagos. MAG is currently working on the implementation of a bio-agricultural plan that promotes the use of alternatives to pesticides (Guzmán & Poma 2015), and scientists are searching for more environmentally friendly control methods, such as biological controls for blackberry and the tropical fire ant. But until these are developed and fully tested, it is essential that we work together to promote the safest and most effective use of agrochemicals.

*The Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock, MAG, was known as the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Aquaculture and Fisheries, or MAGAP, at the time this study was carried out.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and Galapagos Conservancy. We would like to thank the farmers of Santa Cruz for their participation in the interviews. These interviews could not have been conducted without the help of the technical staff of MAG (formerly MAGAP). We also would like to thank Marcelo Loyola, Carolina Carrión, Charlotte Causton and Denisse Barrera from the Charles Darwin Foundation. We are grateful to Jon Witman and Cheryl Hojnowski for revisions of the manuscript. This publication is contribution number 2260 of the Charles Darwin Foundation for the Galapagos Islands.

REFERENCES

Bradshaw CJA, B Leroy, C Bellard, D Roiz, C Albert, A Fournier, M Barbet-Massin, J-M Salles, F Simard & F Courchamp. 2016. Massive yet grossly underestimated global costs of invasive insects. Nature Communications 7, 12986 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12986

Causton CE & C Sevilla. 2008. Latest records of introduced invertebrates in Galapagos and measures to control them. Pp. 142–145. In: CDF, GNP & INGALA, Galapagos Report 2006– 2007. Charles Darwin Foundation, Puerto Ayora.

CGREG 2014. Consejo de Gobierno del Régimen Especial de Galápagos. Censo de Unidades de Producción Agropecuaria de Galápagos 2014.

Guzmán JC & JE Poma. 2015. Bioagriculture: An opportunity for island good living. Pp. 25-29. In: Galapagos Report 2013-2014. GNPD, GCREG, CDF and GC. Puerto Ayora, Galapagos, Ecuador.

Nufarm 2012. Anikil 4 EC, Ficha Técnica Comercial. Nufarm Colombia S.A.

O’Connor M & N d’Ozouville. 2015. Uso de pesticidas en la agricultura en Santa Cruz. Pp. 30-34. In: Informe Galápagos 2013-2014. DPNG, CGREG, FCD y GC. Puerto Ayora, Galápagos, Ecuador.

Toral-Granda, M.V., CE Causton, H Jäger, M Trueman, JC Izurieta, E Araujo, M Cruz, KK Zander, A Izurieta & ST Garnett. 2017. Alien species pathways to the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. PLoS ONE 12(9): e0184379.