Figure 1. A Santa Cruz teacher participates in a workshop about natural science lessons that get students out of the classroom. Photo: Buró Comunicación Integral

Between 2006 and 2013, education in Ecuador improved faster than in most Latin American countries (UNESCO 2009, 2016). However, standardized tests conducted by Ecuador’s National Institute for Evaluation revealed that the performance of young people in Galapagos lagged behind that of their counterparts on the mainland in three core subject areas (mathematics, natural sciences and social studies), as well as in verbal reasoning and abstract thinking.

Since 2016, the Education for Sustainability in Galapagos (ESG) Program has been transforming the outlook for education in the Archipelago, through a strategic alliance between the Ecuadorian Ministry of Education, Galapagos Conservancy, and Fundación Scalesia. The ESG Program provides intensive professional development for educators in all schools in Galapagos, with the goal of improving student performance and strengthening student understanding of the special place in which they live.

In this article I describe the special characteristics of the ESG Program. I also share some personal thoughts about the significance of the change occurring for many of the teachers, and about the exceptional opportunity we have in Galapagos to advance a model for promoting sustainability through formal education.

CONNECTING WITH THE EDUCATION FOR SUSTAINABILITY PROGRAM

In 2014, while serving in the Ministry of Education, I met with representatives from Galapagos Conservancy and Fundación Scalesia, who proposed a tripartite public-private alliance. Through this alliance, Galapagos Conservancy and Fundación Scalesia would mobilize technical and financial resources to strengthen education in the Galapagos Islands, and the Ministry would provide support for program design and logistics, as well as additional funding.

The visitors described an approach that was consistent with pilot projects I had led in the Ministry. They stressed that relatively small size of Galapagos in terms of the number of schools (20), educators (400) and students (7,500), made it a perfect laboratory for the design and validation of a model of teacher professional development with possible relevance for other places. The Ministry of Education agreed enthusiastically with this proposal, and the partners established a workplan that I lost track of when I left my position in the government.

Over a year later, I received an e-mail describing an innovative program that was about to be launched in the Islands. To my surprise, this was the same program I has seen take shape at the Ministry. I was now being invited to take part in the process.

In early 2016 I joined the program as its leader in Galapagos. I was both excited and daunted by the challenges of relocating to the Archipelago and of adapting my experiences in the Ministry to realities in the Islands. I was able to count on the support of a team of 45 external facilitators – experienced educators from mainland Ecuador, Colombia, Mexico, Dominican Republic and the United States, who were selected by the program for their educational philosophy and their extensive expertise in teacher professional development. On April 14, I arrived in Santa Cruz carrying two suitcases: one containing my personal items and the other books, manuals and professional materials.

A UNIQUE PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM

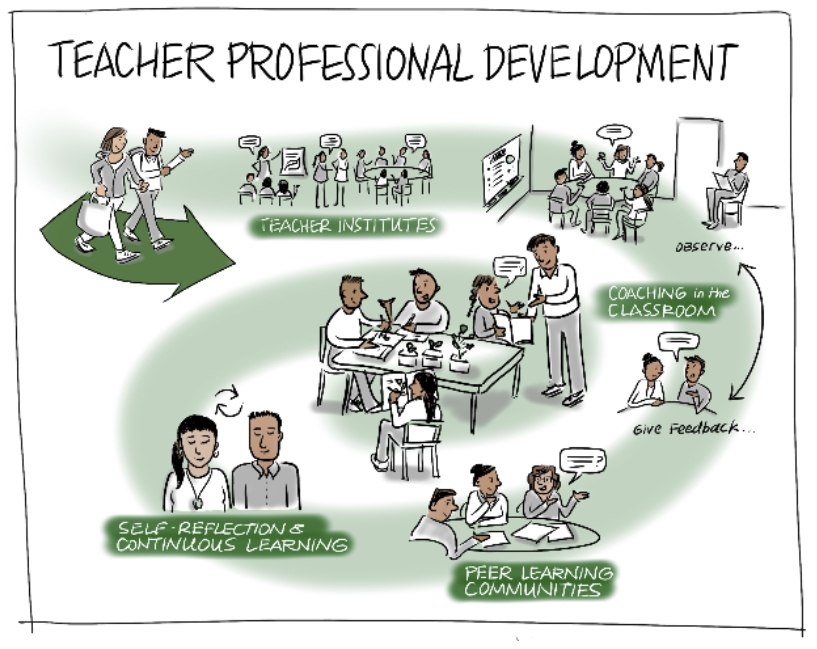

I was attracted to the ESG Program by the way it combines three forms of professional development: in-person workshops (known as Teacher Institutes), Classroom Observations and feedback sessions, and professional Learning Circles (Figure 2). It also promotes Educational Leadership and the principles of Education for Sustainability. There is no other initiative in Latin America that combines all these elements.

Figure 2. The Education for Sustainability in Galapagos Program is unique in its emphasis on professional development via an iterative cycle of in-person workshops, classroom observations, and professional learning circles. Credit: Emily Shepard, Graphic Distillery

The first Teacher Institute took place at the end of April 2016. Teacher Institutes are intensive, five-day workshops led by the program’s external facilitators. Institutes are organized by grade level groupings of the national curriculum (pre-school, early elementary, late elementary, middle school and high school) and by subject (mathematics, science, language and literature, social studies, and English language). For the first time in Ecuador, the Ministry of Education set aside two weeks during the school year for the workshops. Participants include all 375 teachers and 30 school leaders (directors, subdirectors, rectors and vice rectors) of the 20 public, private and municipal schools in the Islands.

During part of each Institute, teachers assume the role of the pupil and “live” classroom lessons that they can later adapt for their own students. During these lessons, external facilitators demonstrate high-impact teaching strategies, such as how to manage group work, use questions to stimulate understanding, and apply different methods to assess student learning. They also share strategies that are specific for certain disciplines. For example, in mathematics, teachers learn how to develop student understanding of abstract mathematical concepts using materials that students can touch and manipulate (Figure 3). In social studies, facilitators share strategies that help students learn to read and think as historians, rather than just memorizing data and dates.

Figure 3. Dr. Arthur Powell, one of the program’s external facilitators, instructs teachers in the use of Cuisenaire rods, which are an excellent way to apply manipulatives for developing understanding of mathematical concepts. Photo: Jonathan Drake/T2T-Global.

Following the first Teacher Institute, I started my work as one of the ESG Program’s three instructional coaches (in Spanish: “líderes pedagógicos”) supporting Galapagos teachers throughout the year. One of our main activities is Classroom Observation. We visit every classroom in Galapagos several times a year to observe teachers as they present a lesson. Following each observation, we facilitate feedback sessions where the teacher reflects on his/her performance and commits to concrete steps to strengthen his/her skills. Each observation and feedback session last approximately three hours.

Learning Circles are the next step in the process (Figure 4). These collaborative work sessions provide an opportunity for teachers to get together to discuss shared needs and reinforce what they learn in the Teacher Institutes and the Classroom Observations. Early in the program, the three instructional coaches led Learning Circles, but teachers are now assuming greater responsibility for managing these meetings themselves. The Circles meet for two hours every two weeks, outside of regular school hours. Most sessions involve between five and 12 teachers.

EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP

Achieving and maintaining significant improvements will require local school administrators and local instructional coaches with the vision and skills necessary to support the continued professional growth of their colleagues. Therefore in June 2018 we began to build capacity in each school to perpetuate Classroom Observations and Learning Circles with their own personnel.

An average of two teachers per school (a total of 40) were selected to serve as local instructional coaches, based on the recommendations of school principals, peers and ESG Program personnel. Four Educational Leadership Institutes were then planned, with the first two implemented in June and October 2018. These leadership institutes allow the 40 coaches-in-training and 30 school principals and vice principals to explore different models of leadership, reflect on their own practices, and develop new tools to lead educational changes in their schools. The institutes are complemented by special learning circles where instructional coaches help coaches-in-training to build the skills needed to identify effective teaching practices and offer constructive feedback.

EDUCATION FOR SUSTAINABILITY

Education for Sustainability is a cross-cutting theme of the program and helps students understand the inter-connectivity of social, environmental, political and economic issues that affect their communities and the broader world. Education for Sustainablity also prepares and motivates students to act on their knowledge to make positive contributions in their communities.

During 2018, we began to work closely with the Ministry of Education to develop a teacher guide to support the design of lessons that connect learning standards in the national curriculum, local examples in Galapagos (flora, fauna, social issues), and global principles of sustainability. Once the guide is tested in Galapagos, the Ministry of Education would like to explore the possibility of adapting it for other parts of Ecuador.

IMPACT ON TEACHERS AND STUDENTS

We are encouraged by the great strides being made by many program participants. I share two examples below. The names of the teachers are fictitious, but the stories are real.

One morning in November 2016, I visited the class of Rómulo, a sixth-grade teacher in Santa Cruz. When I first met him, Rómulo impressed me as a shy person with strong capacity for reflection. During this visit I observed a math class about mass and volume. Rómulo had hidden clues that his students discovered, one by one, as if they were conducting a treasure hunt. Rómulo was the leader of a team of explorers eager to learn, searching for clues in and out of the classroom. During the entire process, his students had big smiles on their faces. During our feedback session, Rómulo told me how thankful he was for the ESG Program and all he is learning with his students. He now demonstrates considerable self-confidence.

The smiles on the faces of Rómulo’s students reflect their discovery that learning can be joyful. I saw this same love of learning while observing María’s sixth grade class, where her students, working in groups, used post-it notes to record the foods they had consumed at lunch, then classified the data according to the nutrients in each food and calculated the percentages of consumption from each food group. Using guiding questions, María helped the students discover the best way to feed themselves without negatively affecting their environment. Their faces full of admiration, the children pledged to tell their parents that “the Galapagos lobster has consumption restrictions that must be respected to assure the sustainability of the resource.” Several children repeatedly asked the teacher: “Are you sure we’re in math class?”

Figure 5. During the October 2018 Teacher’s Institute, more than 275 teachers participated in workshops at the Scalesia Foundation’s Tomás de Berlanga School in Santa Cruz. Foto: Buró Comunicación Integral

FINAL REFLECTIONS

Between April 2016 and the end of December 2018, the Education for Sustainability in Galapagos Program delivered six Teacher Institutes (300 hours in total), 1,500 Classroom Observations (4,500 hours total) and 500 Learning Circles (1,000 hours total) for teachers at every school in Galapagos. Teacher satisfaction and attitude assessments demonstrate a high level of engagement and motivation, stronger relationships between teachers and school principals, and a higher level of “grit” or perseverance to overcome challenges.

During the 2019-2020 school year, the fourth of five years planned for the program, school principals and new instructional coaches will begin to play a greater role in planning and delivering professional development and will launch additional educational improvements in their schools. The program will also begin to analyze data collected on teacher performance. For the first time, we will be able to formally measure our impact.

In the meantime, I would like to share the following recommendations:

Over the next two years it will be important to build mechanisms and incentives to ensure that local educators assume responsibility for the design and delivery of professional development activities (Institutes, Classroom Observations, and Learning Circles) into the future.

Significant time must be invested to organize the hundreds of workshop support materials generated by the ESG Program, to make them accessible to Galapagos educators and for possible replication of the program in other places.

While external support will decrease when the ESG Program is completed, local educators should seek to maintain strong relationships with the 45 external facilitators, most of whom want to continue to support Galapagos teachers over the long-term.

When exploring the possibility of replicating aspects of the program in other parts of Ecuador, the Ministry of Education should consider Galapagos principals and the new instructional coaches as invaluable advisors in the design and implementation of activities.

From time to time we have shared inspirational quotes with program participants that speak to the importance of the teaching profession. One of my favorites is from Brad Henry, former governor of the state of Oklahoma: “A good teacher can create hope, ignite imagination and inspire a love for learning.” Becoming this kind of educator requires enormous commitment and dedication, qualities I see in many of the Galapagos educators with whom we work. Their hard work and enthusiasm assure me that they will take full advantage of this opportunity to make a significant contribution to the long-term protection of these enchanted isles.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank Richard Knab for his review of this article and Ms. Judie Muggia, who has financed the position of Program Leader since the beginning of the Education for Sustainability in Galapagos Program.

REFERENCES

UNESCO. 2009. SERCE: Segundo Estudio Regional Comparativo y Explicativo: los aprendizajes de los estudiantes de América Latina y el Caribe; reporte técnico. UNESCO Office Santiago and Regional Bureau for Education in Latin America and the Caribbean, Laboratorio Latinoamericano de Evaluación de la Calidad de la Educación. Santiago de Chile. 585 pp.

UNESCO 2016. TERCE: Tercer Estudio Regional Comparativo y Explicativo: reporte técnico. UNESCO Office Santiago and Regional Bureau for Education in Latin America and the Caribbean. Santiago de Chile. 420 pp.