Inti Keith[1], Jessica Howard[1], Tomas Hannam-Penfold[1], Sofia Green[1], Jenifer Suarez[2] and Mariana Vera[3]

[1]Charles Darwin Research Station, Charles Darwin Foundation, [2]Galapagos National Park Directorate, [3]Conservation International

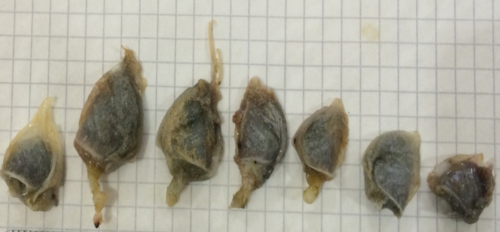

Figure 1. Stalked barnacles attached to a plastic water bottlet. Photo: Sofia Green

In 2016, a new species washed up on the shore of Santa Cruz Island in the Galapagos Archipelago, securely fixed to a piece of floating plastic. Fortunately, the one-centimeter Dosima fascicularis (Figure 2), a non-native species of stalked barnacle, is not invasive. It is unlikely to outcompete other barnacles, take over their habitat, or alter ecosystem food webs. But its ability to reach the Islands attached to plastic debris is a sign of the times, and a new challenge that Galapagos marine scientists are monitoring carefully. An invasive species could harm the Galapagos environment, the economy, or even human health.

Plastic debris has provided a novel and devastatingly abundant habitat for marine hitchhikers, creating diverse communities of species associated with floating plastic and transported over large distances by oceanic currents (Carlton et al. 2017). Roughly 25% of all plastic found at beaches in Galapagos is colonized by at least one plant or animal that has adhered to the plastic surface.

Galapagos is situated at the confluence of several major marine currents, which enables the arrival of species from across the Pacific Ocean. In a place of origin far away from the Islands, plastic refuse tossed in the street can enter storm drains, be carried by rivers and sometimes after years of floating across the ocean, eventually wash up on the shores of this important World Heritage Site.

THE GALAPAGOS MARINE INVASIVE SPECIES PROGRAM

Since 2012, the Charles Darwin Foundation has led the Galapagos Marine Invasive Species Program in collaboration with the Galapagos National Park Directorate, Galapagos Biosecurity Agency, the Oceanographic Branch of the Ecuadorian Navy and the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. This group is working to better understand and mitigate the risk of introducing invasive species into the Galapagos Marine Reserve.

Figure 3. Local children categorizing debris from a beach clean-up for analysis. Photo: Galapagos National Park Directorate

Based on research to date, we now know that there are a minimum of 53 introduced marine animals and plants in Galapagos, ten times the number previously believed to be present (Carlton et al. 2019). In 2015 and 2016, two globally-known invertebrate invaders were discovered in the Islands, the Caribbean spaghetti bryozoan Amathia verticillata (Figure 4) and the Asian seasquirt Ascidia sydneiensis (Figure 5). It is thought these species arrived on boat hulls, but it is also possible that they were introduced by floating marine debris.

Figure 4. The Caribbean spaghetti bryozoan Amathia verticillata. Photo: Linda McCann

Figure 5.The Asian seasquirt Ascidia sydneiensis. Photo: Jim Carlton

Marine debris is any material that floats, including wood and plastic. In 2015, scientists from the Galapagos Marine Invasive Species Program began collecting marine debris each week at Tortuga Bay, Santa Cruz Island, and identifying any attached hitchhikers. This marked the beginning of a marine debris monitoring program, which seeks to enable the early detection of introduced species and assess the potential for plastic waste to transport non-native plants and animals to Galapagos.

MONITORING PLASTIC ACROSS THE ISLANDS

In 2016, we expanded the scope of our marine debris monitoring to the entire Galapagos Archipelago. We created a marine debris drop-off point at the Charles Darwin Research Station on Santa Cruz, where anyone can bring plastic that they find on beaches anywhere in Galapagos. To obtain as many samples as possible, we partnered with organizations that undertake beach clean-up expeditions around the Islands, including Conservation International-Ecuador, Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic and the Galapagos Conservation Trust. We also engaged the Naturalist and Dive Guides Associations, and we distributed flyers to encourage members of the general public and tourists to bring in plastic waste that they find at visitor sites.

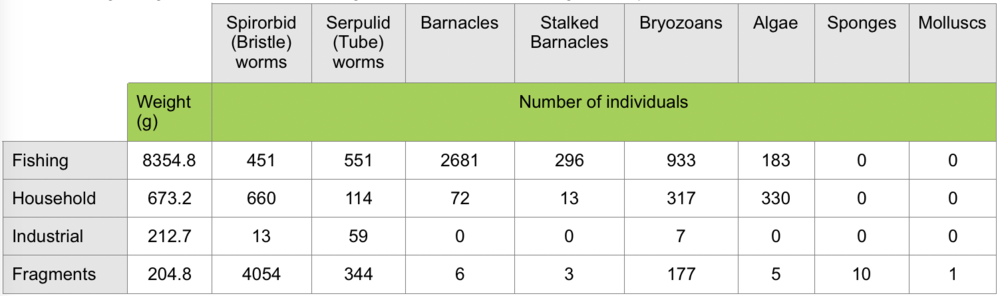

As of February 2019, we have analysed 1,442 samples collected throughout the Archipelago. We’ve documented a total of 11,267 individual organisms that represent 8 groups (Table 1), and we’ve created a database of all organisms found, catalogued by island and type of plastic debris.

Most samples were collected on Isabela, San Cristóbal, and Pinta Islands during plastic waste clean-ups led by the Galapagos National Park, Conservation International, and the Charles Darwin Foundation in 2017 and 2018.

We have categorized plastic debris into four broad types based on its probable origin: plastic linked to fishing, household waste, industrial waste, and unidentified plastic fragments. These categories are not definitive but rather a preliminary classification.

Plastics linked to fishing, such as rope, fishing nets, and buoys, were most likely to be colonized by marine hitchhikers and made up 88% of all colonized plastic by weight (Table 1). Fishing-related plastic also hosted the highest diversity of organisms, with relatively large numbers of each group except sponges and molluscs (Table 1).

Buoys and fuel containers were often colonized by organisms visible to the naked eye, such as large barnacles. Smaller fragments of broken plastic frequently hosted polychaete (segmented) worms known as Spirorbids and Serpulids (Figures 8 and 9). We suspect that our data on polychaete worms underestimates true numbers present, as our sampling was biased toward large plastic objects, which were most noticeable and simplest to collect, and were therefore most frequently brought into our drop-off center.

Table 1. Weight in grams and numbers of organisms found on four categories of plastic debris.

Fortunately, we have detected only one non-native species, the stalked barnacle Dosima fascicularis mentioned at the beginning of this article. Nonetheless, the thousands of individual organisms encountered thus far clearly demonstrate that plastic debris provides an effective means for plants and animals to “raft” into the Galapagos Marine Reserve, underscoring the importance of remaining vigilant. Regular monitoring and research is essential so that early action can be taken for potentially dangerous species that could alter ecosystems, food webs, and human livelihoods.

FUTURE PLANS

The Charles Darwin Foundation will continue the marine debris monitoring program in collaboration with the Galapagos National Park Directorate, Conservation International-Ecuador, Galapagos Conservation Trust, Naturalist and Dive Guides Associations and the general public.

To refine our research, we want to compare those species found on plastics in different areas: close to towns, where plastic debris is primarily of local origin; at tourist sites; and at more remote locations where there is no tourism and where we expect most plastic comes from foreign sources. We thereby hope to understand not only the potential for plastic to introduce new species to Galapagos from faraway sources, but also the role that local litter plays in the redistribution of already established invasive species.

Additionally, we plan to collect plastic waste in the open ocean and on the seabed in order to measure how much plastic is present at the water surface, and how much sinks to the bottom. We will also differentiate between organisms colonizing plastic that has washed ashore and those colonizing plastic in the open ocean, thereby gaining a more complete understanding of the impact that plastic debris is having on the entire marine ecosystem, not just the coast.

Last, we will assess the difference between non-plastic debris, such as wood, and plastic debris in terms of their potential to carry marine species into and throughout the Galapagos Islands.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The risk posed by non-native marine species to the Galapagos Marine Reserve, continental Ecuador, and neighbouring countries should not be underestimated, nor should the amount of research and funding needed to mitigate this risk. We recommend that a regional network be created to coordinate the study of marine plastic debris throughout the Eastern Tropical Pacific region, and to standardize research methodologies in order to ensure comparable results and create consistent management strategies.

We commend the Galapagos community for its initiatives to eliminate plastic waste and urge that they continue. While global efforts are needed to minimize the initial entry of plastic into the ocean, we can take action now to tackle local sources of plastic pollution.

The Galapagos National Park Directorate and its partners organize beach cleanup events throughout the year, which are promoting changes in local attitudes about plastic waste. In conjunction with these clean-ups, local institutions and community organizations should continue efforts to build public awareness about the threat that plastic debris poses to marine ecosystems and to encourage the use of non-plastic alternatives. Through a proactive response to plastic waste, we hope Galapagos will once again serve as an example to the world of how to safeguard marine ecosystems.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Galapagos Conservancy for the continuous support provided since the start of the Galapagos Marine Invasive Species Program. Indispensable partners and collaborators of the program are the Charles Darwin Foundation, Galapagos National Park Directorate, Conservation International-Ecuador, Galapagos Conservation Trust and the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. Funding was provided by Galapagos Conservancy, Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic Fund, the Leona M. and Harry B. Hemsley Charitable Trust and Galapagos Conservation Trust. The authors would like to thank James T. Carlton, PhD, for starting the marine debris component of the marine invasive species program and for his invaluable knowledge in this field. This publication is contribution number 2261 of the Charles Darwin Foundation for the Galapagos Islands.

REFERENCES

Bigg, G & E Rohling. 2000. An oxygen isotope dataset for marine water. J. Geophy. Res.105: 8527-8535.

Carlton JT, Chapman JW, Geller JB, Miller JA, Carlton DA, McCuller MI, Trenemas NC, Steves BP & GM Ruiz. 2017. Tsunami-driven rafting: Transoceanic species dispersal nad implications for marine biogeography. Science 357(6358): 1402-1406

Carlton JT, Keith I & GM Ruiz. 2019. Assessing marine bioinvasions in the Galapagos Islands for conservation biology and marine protected areas. Aquatic Invasions (in press)

Keith I, Dawson T & KJ Collins. 2016. Marine Invasive Species: Establishing pathways, their presence and potential threats in the Galapagos Marine Reserve. Pacific Conservation Biology 22(4): 377-385

Trueman C et al. 2012. Identifying migrations in marine fishes through stable-isotope analysis. Journal of Fish Biology: 81.