Yasuní Chiriboga[1], Richard Knab[2] y Alex Hearn[1]

[1] Universidad San Francisco de Quito – Galapagos Science Center, [2] Galapagos Conservancy

In the vastness of the Pacific Ocean, the Galapagos Marine Reserve was created in 1998 as a refuge to protect marine megafauna from global threats such as industrial fishing and habitat degradation. Pristine beaches in the center of the Reserve provide perfect conditions for green sea turtle nesting. In the north, the iconic Darwin’s Arch is home to large aggregations of hammerhead sharks. The western region hosts giant manta rays and the mystical ocean sunfish, also known as “Mola” or “drunken fish” because of its peculiar way of swimming. These and countless other species make Galapagos a unique underwater paradise (Figure 1).

In the vastness of the Pacific Ocean, the Galapagos Marine Reserve was created in 1998 as a refuge to protect marine megafauna from global threats such as industrial fishing and habitat degradation. Pristine beaches in the center of the Reserve provide perfect conditions for green sea turtle nesting. In the north, the iconic Darwin’s Arch is home to large aggregations of hammerhead sharks. The western region hosts giant manta rays and the mystical ocean sunfish, also known as “Mola” or “drunken fish” because of its peculiar way of swimming. These and countless other species make Galapagos a unique underwater paradise (Figure 1).

Many of these species are migratory and vulnerable as soon as they leave the protected waters of the Galapagos Marine Reserve (Hearn et al. 2014, Hearn and Bucaram 2017). In such cases, what real benefit does the Reserve provide?

Figure 1. Some of the megafauna that inhabits the Galapagos Marine Reserve. From left to right: green sea turtle, hammerhead shark, ocean sunfish, giant oceanic manta ray. Source: Shark Count Galapagos

For example, some experts believe that shark populations have declined in recent decades despite the existence of the Marine Reserve (Schiller et al. 2014). Others believe that shark populations have recovered thanks to the large size of the Reserve and the management measures that have been implemented (Wolf et al. 2012).

It is unfortunately very difficult to know which view is correct, since there has been no consistent monitoring of megafauna populations either before or after the establishment of the Marine Reserve. There are four main reasons for this: the vast size of the protected area, the relatively limited number of researchers, the high mobility of megafauna species, and the significant natural variability that affects population counts. Some purely scientific efforts have managed to capture a snapshot (Hearn et al. 2014, Salinas et al. 2016, Peñaherrera et al. 2017, Acuña et al. 2018), but they all face the same problem: they are impossible to sustain over time.

CITIZEN SCIENCE: A POWERFUL CONSERVATION TOOL

A few years ago, our gaze drifted to our neighbors at Cocos Island in Costa Rica, a small site half-way (about 700 km) between Galapagos and Central America. Three dive tourism boats have been operating there for more than 25 years. Dive masters in Cocos serve as citizen scientists, registering their sightings of marine megafauna during each dive and sharing their data with research projects.

Recent analysis of the Cocos database revealed that despite the 12 miles of marine reserve that surrounds Cocos Island, hammerhead shark populations declined significantly over the past two decades. Meanwhile Galapagos sharks and the tiger sharks have increased in number (White et al. 2015). These results demonstrate the importance of consistent, long-term monitoring.

In 2008, our inter-institutional team at the Galapagos Shark Research and Conservation Program initiated censuses like those of Cocos Island, which included counts of sharks, sea turtles and other megafauna. We even involved dive guides in the process, in order to expand our geographic reach and the frequency of data collection (Hearn et al. 2014). However, we were unable to sustain the involvement of divers over the long-term.

With the precedent on Cocos Island and our initial experiences in Galapagos in mind, in 2016, the Universidad San Francisco de Quito-Galapagos Science Center, Galapagos Conservancy and the Galapagos National Park Directorate tried once more, this time taking advantage of new technology. Together we developed and launched Shark Count Galapagos, an application (App) for tablets and smartphones that facilitates reporting of megafauna sightings at dive sites around the Galapagos Marine Reserve.

Shark Count aims to unite researchers, dive guides and tourists so that together, as citizen scientists, we can secure the spatial and temporal coverage that is so essential for marine monitoring. Over time, Shark Count will allow us to establish a baseline against which we can identify changes in the abundance and distribution of megafauna in the Galapagos Marine Reserve. This public data will help decision-makers at the Galapagos National Park to take timely action to conserve these species.

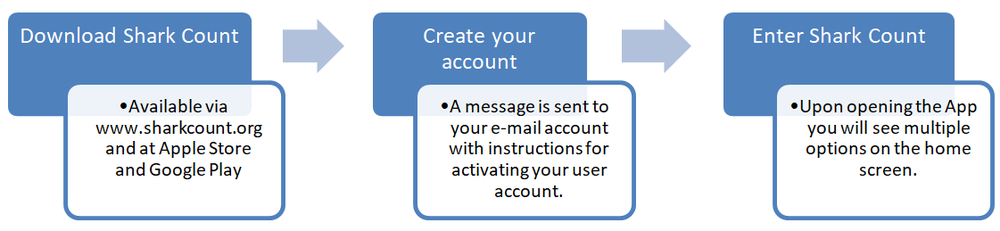

HOW DOES THE APP WORK?

The Shark Count app is free and easy to use.

On the home page users find a link to an identification guide that describes the megafauna most commonly observed in the Galapagos Marine Reserve. The guide includes images and background information about several species of sharks, fish, sunfish, turtles and rays that assists in their identification.

Users enter observations on the New Dive tab, by selecting the appropriate dive site from a dropdown menu that includes sites chosen for their popularity among dive tourists and their importance for research. After each dive, users enter the number of each species observed and dive conditions (water temperature, clarity and any anomalies) and can choose to upload photographs.

An Internet connection isn’t necessary to enter dive observations. Data is stored on the user’s phone and uploads automatically when an Internet connection is available. Shark Count works even in remote sites like Darwin and Wolf Islands, where there is no Internet signal.

The menu on the home page of the app also provides the option to view data entered by other users. This makes it possible to determine the best time of the year to see particular species at a particular dive site. There is also an option to view sightings on a map.

WHY USE SHARK COUNT?

Shark Count is useful for many users of the Galapagos Marine Reserve. If I’m a guide, it helps me in my day-to-day work, by allowing me to see which species were recently spotted at each dive site. This helps me to prepare pre-dive briefings for my clients and stay up-to-date on the species that we will likely observe. Shark Count also helps me talk with my clients about the special nature of the Marine Reserve and its importance for migratory species. Longer term, it will allow me to evaluate population trends of these species, and even to use the data in the app to request management measures from authorities if I detect worrisome patterns.

If I’m a tourist, Shark Count helps me plan my vacation by learning about the best sites and seasons to see different species. It also helps me to talk with my guides about the threats and the conservation status of these species. It adds value to my experience, by allowing me to contribute to conservation by reporting my sightings.

If I work with an organization or institution focused on responsible management of the Galapagos Marine Reserve, I want to understand the role of the Reserve in the protection of key species, and I need an economically sustainable way to monitor their long-term presence and abundance. I also need to be able to respond to the needs and concerns of users, whether they are guides, tourists or dive operators. With Shark Count, conversations can become more technical, because we all see the same data. If necessary, I can implement management measures in real-time at specific sites.

PROMOTING THE APP

After launching Shark Count in July 2017, we conducted short promotional campaigns among members of the dive guide community. We circulated posters and an instructional video among dive agencies on Santa Cruz and San Cristóbal Islands. We also met individually with divers who expressed interest in downloading the app and gave a Shark Count t-shirt to those who put the app to use.

Our promotional campaigns were short, but they managed to familiarize the dive guide and naturalist guide communities with the existence and purpose of Shark Count.

ACHIEVEMENTS DURING YEAR ONE

Just one year after launching Shark Count, we have collected double the number of observations made by scientists and collaborators between 2008 to 2015. When we launched the app, we included 392 historical data reports. Twelve months later, we have over 1,000 reports encompassing over 53,000 sightings of 10 target species.

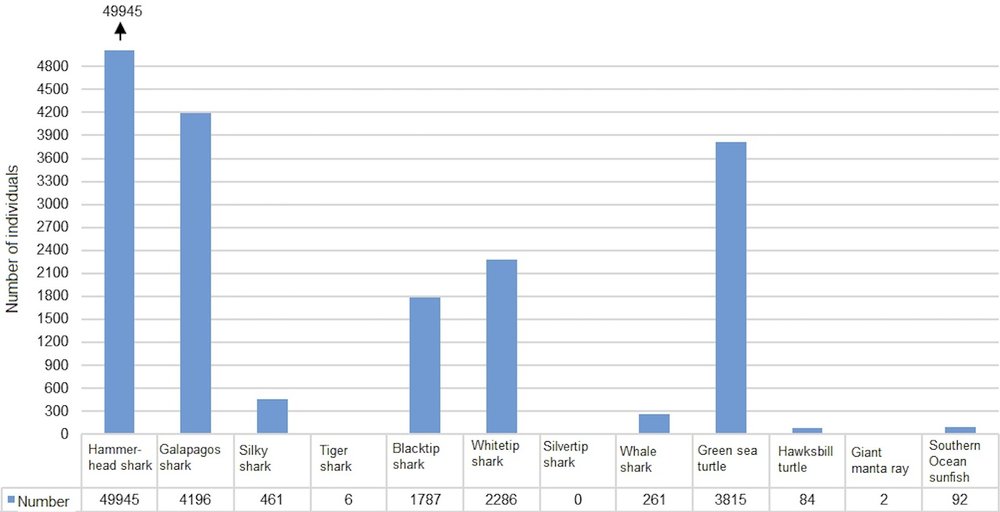

Figure 2. Total number of observations of different species, as reported via the Shark Count App.

Figure 2 shows the number of species that have been recorded so far with the help of citizen scientists. Hammerhead sharks have been reported most frequently, followed by green turtles and Galapagos sharks. Divers have reported several observations of the silver-tipped shark (Carcharhinus albimarginatus) and the giant manta ray. To date, we have received only a handful of observations of tiger sharks, but this isn’t surprising, since this species is rarely observed by divers, despite its presence in areas such as southern Isabela and northern Santa Cruz.

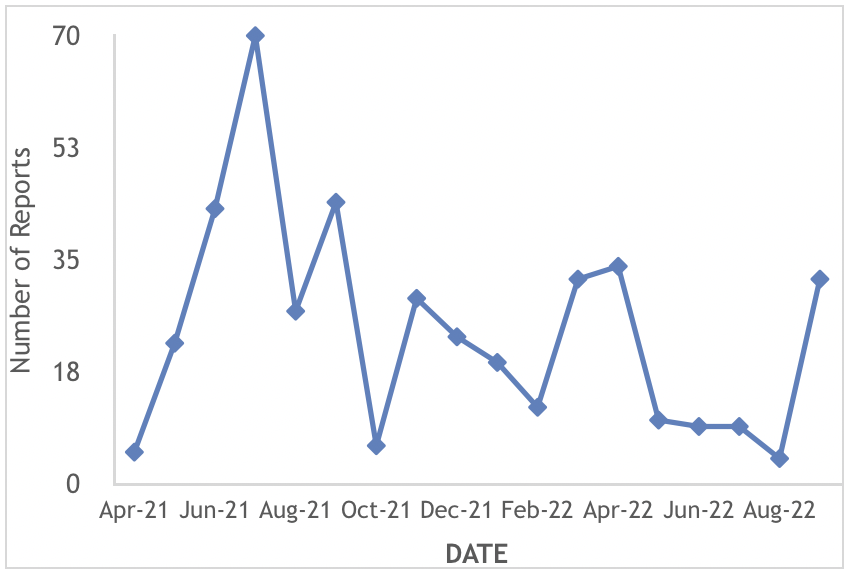

With the data collected thus far, we can begin to establish seasonal patterns of some of species, such as the hammerhead shark, which is reported with greater frequency during cooler months (Figure 3).

We have received the largest number of reports from Darwin and Wolf Islands. These sites are especially important to researchers, who have generated most of the data from these locations. Dive guides have entered significant numbers of reports from Gordon and Baltra Rocks, including Mosquera and Daphne Minor, which are popular dive tourism sites known for the presence of sharks, rays and turtles.

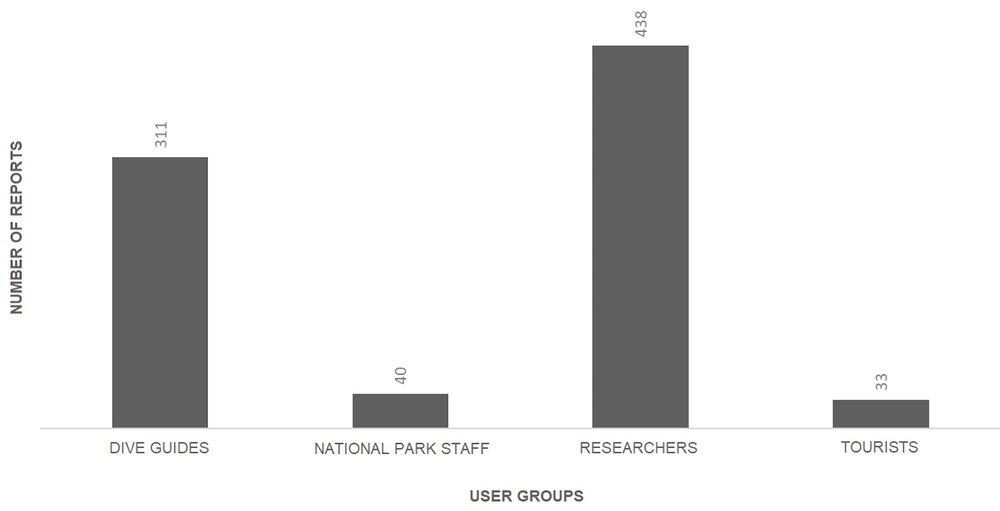

User data tells us that peak use of Shark Count generally occurs during our promotional campaigns and the high season for diving (Figure 4). Dive guides provide reports more frequently than tourists (Figure 5). While the quality of the information presented by a guide tends to be more accurate and consistent than that of dive tourists, we would like to increase the number of participating tourists and use the data of guides and scientists as quality control.

Figure 4. Trends in app use by month, since launch of Shark Count in 2017.

Figure 5. Number of reports entered by different users. Naturalist guides are included in the National Park Directorate figures. The tourist category refers to dive tourists only.

PROSPECTS FOR THE FUTURE

We are currently working on developing Shark Count 2.0, which will include new sites and new species, such as the Galapagos bullhead shark (Heterdontus top) and several species of rays.

The new platform will also provide snorkelers the opportunity to join our team of citizen scientists. Given the numbers of snorkelers in the Islands, their participation will help us to gather significant amounts of information on a larger number of species. This data will be analyzed separately from observations made by divers.

We will also expand our promotion of Shark Count beyond the dive guide community, to include naturalist guides and tourists. We are planning additional interactive tools to increase and maintain participation among different user groups.

Based on our initial success with Shark Count, we will work with Migramar, a network for research and conservation of migratory marine species in the Eastern Tropical Pacific, to replicate our model in other parts of the region. Specifically, we are preparing versions of Shark Count for Isla de la Plata (coastal Ecuador) and the Revillagidedo Archipelago (Mexico).

Within two to three years we believe that Shark Count will collect enough data to establish a spatial baseline of the abundance and distribution of key marine species during both the cold and warm seasons. From this baseline, we will begin the long-term monitoring process, to measure trends over decades and to continually evaluate the protection provided by the Galapagos Marine Reserve.

FINAL REFLECTIONS

Shark Count is already demonstrating the great value of citizen science. The involvement of guides and tourists in our research has allowed us to obtain results that would not be possible through efforts led by scientists alone. Citizen science is also empowering the public as an agent of change, and facilitating meaningful interaction between scientists, society, and policymakers for the long-term benefit of conservation in Galapagos. The challenge will be to maintain our initial momentum, to ensure that Shark Count becomes a tool that guides, park rangers, and marine scientists use on a daily basis, and to encourage large numbers of dive and snorkel tourists to use our app to support conservation during their visits to our wonderful islands.

REFERENCES

Acuña-Marrero D, Smith ANH, Salinas-de-Leon P, Harvey ES, Pawley MDM & MJ Anderson. 2018. Spatial patterns of distribution and relative abundance of coastal shark species in the Galapagos Marine Reserve. Marine Ecology Progress Series 593: 73-95

Hearn A & SJ Bucaram. 2017. Ecuador’s sharks face threats from within. Letters to Science 358 (6366):1009-1009

Hearn A, Acuña D, Ketchum JT, Peñaherrera C, Green J, Marshall A & G Shillinger. 2014. Elasmobranchs of the Galapagos marine reserve. En The Galapagos Marine Reserve (eds J Denkinger & L Vinueza). Pp. 23-59. Springer press.

Peñaherrera-Palma C, Espinoza E, Hearn A, Ketchum J, Semmens J & A Klimley. 2017. Report on the population status of hammerhead sharks in the Galapagos Marine Reserve. En Galapagos Report 2017. Pp 125-129.Galapagos Conservancy/Galapagos National Park.

Salinas-de-León P, Acuña-Marrero D, Rastoin E, Friedlander AM, Donovan MK & E Sala. 2016. Largest global shark biomass found in the northern Galápagos Islands of Darwin and Wolf. PeerJ 4: e1911.

Schiller L, Alava JJ, Grove J, Reck G & D Pauly. 2014. The demise of Darwin’s fishes: evidence of fishing down and illegal shark finning in the Galapagos Islands. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshwat. Ecosyst. 15: 431–446.

White ER, Myers MC, Flemming JM & JK Baum. 2015 Shifting elasmobranch community assemblage at Cocos Island – an isolated marine protected area. Conservation Biology, 29(4), 1186-1197

Wolff M, Peñaherrera-Palma C & A Krutwa. 2012. Food web structure of the Galapagos Marine Reserve after a decade of protection: insights from trophic modeling. En The Role of Science for Conservation (eds. M Wolff & M Gardener). Pp. 199. Routledge, UK.